'Wolfenstein,' Robert Antelme, and the inner lives of Nazis

How the negation of our villains' humanity inadvertently helps to exonerate them

Even if you don’t give a rat’s ass about Wolfenstein, this winds up opening up into a broader assessment of Nazis in popular culture—Ed.

Well, it's official, I guess I'm GamerGate now. I'm as surprised as anyone, but once I played Wolfenstein: The New Order for a mere hour or two I suddenly concluded that, wow, you know what? Maybe video games shouldn't be allowed to be about anything anymore. Maybe those guys who sent game devs death threats for daring to have “themes” had the right idea after all! Every game dev with a BA must be immediately purged!

I had my suspicions about Wolfenstein: The New Order when the initial fanfare began over a decade ago and I was told that the game series that once boasted a Mecha-Hitler was now somehow saying cogent things about fascism and the Holocaust. I suppose crazier things have happened (like when mid-tier tac shooter series Spec Ops was rebooted as the interactive anti-war polemic Spec Ops: The Line for example) but I remained unconvinced, and so I never bothered to play the new Wolfenstein. That is, until I was able to buy it for under $5. Playing it confirmed every suspicion I’d ever had about the title and then victory-lapped them. The New Order is not only a bad game, but in fact highlights a lot of the problems inherent in the contemporary social imagination of what fascism looks and feels like.

These days everybody likes to go “ludonarrative dissonance this” and “ludonarrative dissonance that,” but Wolfenstein: The New Order has such fucking pronounced ludonarrative dissonance, that I could have sworn I was playing a completely unrelated video game simultaneous to the terrible movie I was watching—like I was playing Doom while Pearl Harbor was on in the background, and both were overlaid on top of one another on the same monitor.1 The levels are all so damn short—just when I’m getting to enjoy one, I’m plunged into another fucking ten-minute cutscene, and whilst the gameplay is big epic shooty-shooty bang-bang rah-rah shit with the expected occasional giant Mecha-Nazis and little set piece flourishes, the cutscenes will be these painfully-serious bores where protagonist BJ gives us a monotone monologue about all of his pain and angst to remind us that, actually, World War II was a serious bummer and not fun at all.2 Damn it BJ, just drown your sorrow in liquor like a good mid-20th-century man and shut up while I seal this Nazi’s passport to hell with a lead stamp to the forehead.

Often the gameplay itself is filled with tonal contradictions that really don’t feel intentional, and are occasionally downright offensive. There’s a “fun” section early on where we try to escape just in time from a room where an incinerator has been activated—an incinerator that has the purpose of disposing of the bodies of ostensible Holocaust victims. You literally “escape the ovens.” And it’s played for thrills. Cute. Eventually BJ is made a temporary vegetable and winds up in a care facility in Poland. Years pass, and BJ is eventually able to make a full recovery—just in time to start watching some Gestapo execute a bunch of mentally-infirm people. Fun game!!!!! We all having fun yet????? This is a game that features a big crunchy metal guitar soundtrack, and then you’re shooting Nazis in the hallways of a hospital over the bodies of patients they’ve just Aktion T4’d. I guess it beats the Diving Bell and the Butterfly simulator the game was teasing me with, but, call me picky, I don't like it when my food touches, and I'd rather not get this horseradish into my pop rocks. It reminds me of scenes in the Gears of War franchise where your Choo! Choo! Frat-Brother Monster-Killing Train would be derailed every once in a while because a traumatized POW decided to commit suicide with a sawed-off shotgun in front of you—“good taste” executed by someone who has astoundingly bad taste.

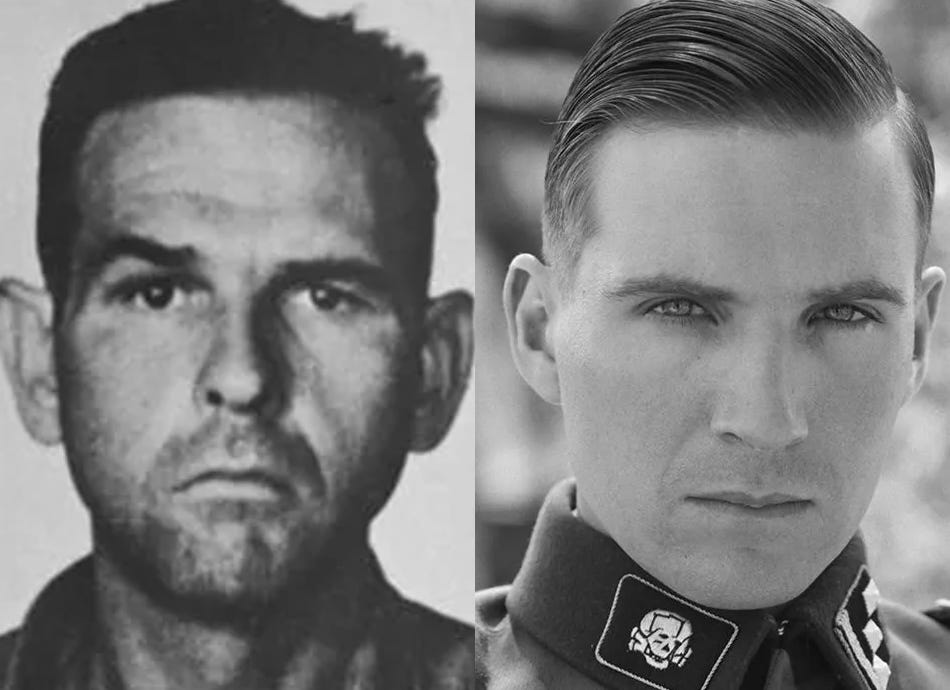

The game reminds me of another attempt-at-“good-taste”-executed-by-someone-with-astoundingly-bad-taste about this very same subject, Schindler’s List, with one particular point of overlap being how the two works deal with the task of representing Nazis. Echoing Spielberg’s naïve choice (though perhaps a sympathetic choice) in Schindler to depict the Nazis as heartless psychopaths, Wolfenstein: The New Order opts to dehumanize the Nazis to the point of making them B-movie monsters, a decision which effectively lets them off the hook in the process. Being inhuman, they are not subject to human morality, they are animals, they are a force of nature. A Nazi like The New Order’s primary antagonist, Deathshead, an obvious stand-in for Mengele, becomes as inevitable and mindless as a hurricane. This is communicated through every interaction we have with him, every word that comes out of his mouth, his sneering tone of voice, even just the way he looks. Just take a look at this picture of Wolfenstein’s Deathshead.

Grim, isn’t he? His smile is filled with malice, why, I’m sure he’s just gotten through euthanizing a litter of puppies Pete-Buttigieg-style. Let’s go back to the man Deathshead is based on—this is a photo taken of Josef Mengele, in hiding from Nazi hunters after having tortured and murdered his countless concentration camp test subjects and gotten away with it, with his son Rolf, having a little family vacation:

Now consider Deathshead again. Can one imagine Deathshead smiling, not with sadism, but because he is enjoying spending time with his family?3 Can we imagine Deathshead on vacation? The real Mengele was a lover of music and an avid skier. Can we imagine Deathshead to have pastimes or hobbies? Does he play with trains? Collect stamps? Does Deathshead have human interactions wherein he does not spend the entire conversation maniacally praising the Third Reich and the purity of the Aryan race? When he goes out to eat, how does he speak to the wait staff?

To return to the example of Schindler’s List, let us consider the case of the film’s principal antagonist, the real-life concentration camp commandant Amon Göth. Göth’s girlfriend Ruth Kalder was emotionally-devastated by her lover’s execution after the war and kept a photo of him above her bed for the rest of her life. She described their relationship as “a wonderful time,” and said that “my Amon was king, and I was his queen.” The day after being interviewed for a documentary about Oskar Schindler, Kalder committed suicide, likely being unable to reconcile her feelings for a man who had simultaneously lived a life as a mass-murdering sadist. When we watch Schindler’s List, can we imagine Göth as a man capable of loving and being loved? I suppose it was more important to make sure the actor playing him was sexy, even if the original man was not.

Spielberg really leans into making Göth a force of inhuman nature. His decision to focus on Göth’s shooting of random prisoners from his balcony as a chief example of his monstrosity has the effect of framing his actions as “random,” so thoughtless and erratic as to be analogous to cruel natural luck. The truth is that such moments from Göth were but petty singular instances in a process that was entirely deliberate, calculated, and methodical, requiring cool rationality and human ingenuity to execute: mass murder in the first degree.

My “favourite” Nazi concentration camp narrative (insofar as you can have a “favourite” one) is Robert Antelme’s The Human Race, his account of his time as an inmate at Buchenwald and Dachau. It is an incredibly emotionally complex book, no small feat for someone who had survived a process so emotionally insurmountable. Throughout the book, and unlike many testimonies I’ve read, Antelme seeks desperately to find the humanity in his oppressors—not to exonerate them, but to open them up to judgement. Obviously the dehumanization of the victim was an important part of the Nazi’s extermination campaign, as it allowed them to proceed with their crimes without the friction caused by identifying with their victims as fellow humans. However, what is sometimes less obvious is how this process also functions in the inverse: that when carrying out systematic violence, individual agents of the system also depend on being anonymized—itself a process of dehumanization. In fact, the anonymity of the perpetrator is sometimes even more important to the project than that of the victim because it shields them from the potential consequences of future judgement, and the burden of self-reflection (and thus, the voice of their consciences). As Antelme describes:

For a moment, I was designated here directly, they addressed me alone, I had specifically been called upon—I, irreplaceable! And I appeared. Someone was found to say ‘yes’ to this noise, which was at least as much my name as I was myself, here. And it was necessary to say yes in order to return to the night, into the faceless stone figure.4

The SS are figuratively faceless, while displaying their power to arbitrarily identify the ones they oppress at their own behest.5 The prisoner is both no one and (upon their summoning) the only one; the SS transform both states into instruments of domination. The system depends not on the total deprivation of identity, but in fact this oscillation. The oppressor’s anonymity is not a loss of self, but a weaponized condition, a facelessness that ensures impunity and allows for the mechanical execution of cruelty, like (to put in extremely mundane contemporary terms) the anonymity of an internet troll.

A particularly surreal example of this tension is the anecdote in the book in which a drunk SS officer proceeds to torture a number of prisoners by forcing them to do calisthenics, beating them when they fail to keep up. The officer, laughing at them, is then pathetically joined by the nervous laughter of his own victims, exemplifying a sort of nervous circuitry that binds the oppressor and the oppressed. Everything loses sense. The victims possess a neurotic desire to be “in on the joke,” as it were, of their own suffering, to identify as a means of survival with their own victimizer who beats and laughs at them, who in turns seems to sink into delirium as he begins to, frustrated, kick the air. Cruelty makes cruel men out of those who wield it. The cognitive dissonance it induces drives a frustration that drives more cruelty, and so on. This is sustained because no matter what he does to torment them, no matter how much he may try to dehumanize them, he in turn affirms their shared humanity by doing this:

He finds them there, breathless but intact, in front of him. He hasn’t made them disappear. For them to stop looking at him, he’d have to take out the revolver, kill them. He stands there for a moment, looking at them. No one moves. He’s silent. He nods. He’s the strongest, but they’re there, and they have to be there for him to be the strongest [...]6

Here’s an excerpt from Maurice Blanchot’s essay/conversation “Humankind,” which deals with Antelme’s book specifically, and touches on this theme:

[...] the relation of the torturer to his victim, about which so much has been said, is not simply a dialectical relation. What limits his domination first of all is not his need of the one he is torturing, be it only to torture him; it is rather that this relation without power always gives rise, face to face and yet always infinitely, to the presence of the Other [l’Autre].7

The process of dehumanizing the Other is always frustrated by the fact that this process simultaneously affirms the Other’s humanity. This acknowledgement always exists within the act and cannot be snuffed out. It also, through this same process, condemns the oppressor by exposing this humanity as shared. One of the desires of the oppressor is to reduce themselves to a part of a faceless mass and remove themselves as individuals from the process, to grant themselves a metaphysical alibi, a quasi-divine parallel of “I was only doing my job.” As Blanchot puts it:

What force would want is to leave the limits of force: elevate itself to the dimension of the faceless gods, speak as fate and still dominate as men. [The oppressed’s] last recourse is to know that he has been struck not by the elements, but by men, and to give the name man to everything that assails him.

The SS are often represented as indivisible, through which we grant them what they had hoped to achieve; they are portrayed as little more than the blueprint of a uniform, the manifold faces of a single entity, an oppressive and indomitable force that, like Spielberg’s Göth, goes beyond human evil and become a natural evil. In Wolfenstein: The New Order, for instance, Nazis’ faces are rarely shown, as almost all of the enemies in the game wear masks, making them literally faceless, inhuman representatives of a dark mass, endlessly repeated nobodies. The game’s director, Jens Matthies, had the gall to say of the game that “at its core, it’s kicking Nazi ass. In the most pure sense.” Except it’s not. No Nazi ass is kicked. I saw a bunch of “asses” but no discernible “Nazis” at all, just interchangeable punching bags. Even the game’s official artwork unintentionally works to reinforce this perspective of the Nazis as an anonymized collective shadow:

This is an extremely childish aesthetic decision that could only arrive out of the most painfully-ignorant and cowardly artist, too squeamish to look darkness in the face. Again, here’s a photo of some actual Nazis:

Wow, they look like they’re having a grand old time. Not only can we see their human faces, but they’re remarkably-expressive, goofy even, filled with mirth and joie de vivre. Now feel the chill run up your spine when I tell you that this is a photo taken at Auschwitz. A stupid black gas mask is a cartoon, a pathetically-juvenile attempt to present what real evil looks like—this is what real evil looks like, the smiling faces of happy people fresh from incinerating children’s bodies in a fucking oven.

The mistake is in believing that these details of the Nazis’ humanity somehow exonerate the men who committed the acts. They do not. It is their humanity which damns them, their ability to care and their deliberate choice not to. The Nazis are culpable because the Nazis were human. It is extremely disturbing to consider this fact because their being is such a disgusting perversion of humanity that we naturally want to distance ourselves from it, we want the Nazis to be inhuman because we feel some subconscious sense of complicity by the simple fact of our being of the same species. However, to deny the Nazis’ humanity establishes a faulty foundation upon which any other analogous criminal may have their monstrous acts negated by simply demonstrating a recognizable humanity. This is practiced by the IDF constantly, by the parade of perverted freaks they show us doing cute TikTok dances and the like. An evil person wouldn’t have friends, right? An evil person wouldn’t do a silly little dance, would they?

[Everyone in the above video is going to burn in hell for all time. Also they have no fucking rhythm].

Consider this anecdote

highlights in First As Tragedy, Then As Farce:Our most elementary experience of subjectivity is that of the “richness of my inner life”: this is what I “really am,” in contrast to the symbolic determinations and responsibilities I assume in public life (as father, professor, etc.). The first lesson of psychoanalysis here is that this “richness of inner life” is fundamentally fake: it is a screen, a false distance, whose function is, as it were, to save my appearance, to render palpable (accessible to my imaginary narcissism) my true social-symbolic identity […]

Ideological “humanization” (in the sense of the proverbial wisdom “it is human to err”) is a key constituent of the ideological (self-)presentation of the [IDF]. The Israeli media love to dwell on the imperfections and psychic traumas of the Israeli soldiers, presenting them neither as perfect military machines nor as superhuman heroes, but as ordinary people who, caught up in the traumas of History and warfare, sometimes make errors and lose their way. For example, when in January 2003 the IDF demolished the family home of a suspected “terrorist,” they did so with accentuated kindness, even helping the family to move their furniture out before destroying the house with a bulldozer. A similar incident was reported a little bit earlier in the Israeli press: when an Israeli soldier was searching a Palestinian house for suspects, the mother of the family called her daughter by her name in order to calm her down, and the surprised soldier learned that the frightened girl’s name was the same as that of his own daughter; in a sentimental outburst, he pulled out his wallet and showed her picture to the Palestinian mother. It is easy to discern the falsity of such a gesture of empathy: the notion that, in spite of political differences, we are all basically human beings with the same loves and worries neutralizes the impact of the activity the soldier was engaged in. As such, the only proper reply of the mother should have been: “If you really are a human being like me, why are you doing what you are doing now?”

The “richness of our inner lives” is a shield we utilize to dispel the notion that we could ever be complicit in evil, because we are so enamoured by our complexities, “we contain multitudes” and all that (I have addressed the frivolous misuse of that Whitman quote in a previous post). It is of utmost importance that this notion be challenged, because it is one of the fundamental psychological pillars of evil. These IDF soldiers have interior lives, they are people who love and are loved, they are people with interests and families, they are people with senses of humour, they are people who have surely at times expressed compassion and kindness to others—and they deserve no remorse. Their humanity is what makes them guilty, and, like the SS before them, this is why they too deserve to die.

Paul Verhoeven once described his adaptation of Starship Troopers as cinema from a world where the Nazis won. Wolfenstein: The New Order is a video game from a world where the Nazis won, if not militarily then ideologically; that is to say, a world where the Allied forces defeated the Nazi war machine but subsumed its ideological elements into their own. What’s so funny about this hypothetical world is it’s the one we’re currently living in and always have lived in. Wolfenstein: The New Order is Nazi propaganda that Leni Reifenstahl could only dream of. It accomplishes the exoneration of the Nazis by way of their reduction to natural evil, and it makes doing evil easy by framing such acts as mostly the purview of the unthinking human animal. And, I mean, when you think about it, The New Order really is the perfect game for the Zionists, as it is only vaguely concerned with what actually happened during World War II and the Holocaust. Like the Zionists, The New Order turns World War II into an exciting narrative experience culminating in revenge, catharsis, and glory. The Israelis kill Eichmann, BJ kills Deathshead, and they all lived happily ever after. The villains are dastardly and inhuman, they are easy to dispense of because they are expressly shown to have the interior lives of rabid animals or forest fires. World War II becomes an adventure story, the genocides perpetrated by the Nazis become an Act 2 low point, and everything works in service of the heroic, final triumph. Why do we use the term “Holocaust”—a “burnt offering”? Because we cannot contextualize this kind of suffering as anything other than teleological. As possessing a purpose. It was a sacrifice, an offering up of something presumably for something else. But for what? The answer to that question can be used to facilitate all sorts of grotesques. Israel, for instance, has been proffered as a simple answer to “what it was all for.”

Gamers can’t wait for their medium to ascend to “respectability,” but to put it into a pop culture idiom they’d be more likely to understand: Not ready are you. A game like this one has less of substance to say about the fascism than Nazis at the Center of the Earth or even a Nazi-themed porn flick, and yet Wolfenstein: The New Order was released to rapturous acclaim from the gaming press—including from some critics I actually respect. It all just came off like the kind of embarrassing display of over-compensation gamers participate in endlessly (something which I’ve already discussed at length while talking about a truly objectionable piece of shit game, The Last of Us). The New Order is, at best, a farce. At worst, it is a total perversion of history and justice for a cheap thrill that winds up ironically encouraging the very thing it thinks it’s against.

FOR MORE ON VIDEO GAMES AND ONTOLOGICAL EVIL

'Good Girl Gone Bad' and the fascism of the self

Slowly, however, the game begins to take a turn. Eventually even I have lost control of Ashley. She is beyond my influence. The game no longer presents me with options to “do the right thing”—I can only sin. I can only transgress. I have no choice but to do blow every day, the game doesn’t even let me say “no” anymore, there is no longer an option to abstain, Ashley merely “does.”

The actual game part (which is not really the focus of this article, hence me addressing it in this footnote instead) is not particularly up to snuff for me. For a game this shooty-shooty rah-rah I expect the level design to pull me by the hand into each successive engagement so I can go shooty-shooty rah-rah some more without delay, but I found myself constantly having the action broken up by moments of “…hang on, where do I go next? Where’s the door out of this room?” though this is ultimately a problem with many games of its era.

There’s a trend in “feel bad games,” ostensibly “fun” games like Wolfenstein or Battlefield 1 or whatever else that require you to suffer and feel bad in order to have fun and feel good later. I’ll one day write something more substantial about this.

Ed. Note (from ): You make a good point, but it must be said that Mengele looks like a satanic rat in that pic.

Originally:

Un instant, j’ai donc été désigné ici directement, on s’est adressé à moi seul, on m’a sollicité spécialement, moi, irremplaçable! Et je suis apparu. Quelqu’un s’est trouvé pour dire ‘oui’ à ce bruit qui était bien au moins autant mon nom que j’étais moi-même, ici. Et il fallait dire oui pour retourner à la nuit, à la pierre de la figure sans nom.

Because I feel the need to justify picayune translation choices I made here, I added the em-dash before the repetition of “I” only because the reflexive “moi” here should be translated as “I” and the em-dash makes that line more readable in English I think.

Antelme also identifies a power in his own anonymity, but we won’t get into that here.

Originally:

il les retrouve là, essoufflés mais intacts, devant lui. Il ne les a pas fait disparaître. Pour qu’ils ne le regardent plus, il faudrait qu’il sorte le revolver, qu’il les tue. Il reste un moment à les regarder. Personne ne bouge. Le silence, il l’a fait. Il hoche la tête. Il est le plus fort, mais ils sont là, et il faut qu’ils y soient pour qu’il soit le plus fort; il n’en sort pas.

I snipped the “il n’en sort pas” off in my citation, but leaving it here in the untranslated excerpt just cause. It’s not an unimportant clause, I mostly cut it for flow.

Blanchot is using Levinas’s contrasting Autrui and l’Autre—both meaning “Other”—in this essay/conversation, hence the specification in the parenthetical. Again, we regrettably will not be touching on that, though it does lend an interesting aspect to the discussion.

Thank God, I thought I was the only one. The critical and commercial acclaim of TNO always made me feel like I was a participant in some sort of highly convoluted hidden camera show, waiting futilely for a punchline that never arrived. The game itself made me feel queasy, and for roughly the same reasons as you: it tries to have its cake and eat it too, wanting to both dispense the same ol' cheap pulp thrills that the series used to serve and at the same time, Say Something Important About An Important Subject (To Prove We're Actual Artists(tm)), which makes the tonal whiplash absolutely staggering. These are actual fascists, so we need to present a plausible view of what life under a thousand year Reich would be... but oops! That's too depressing and not actually empowering at all; we need to keep the revenge fantasy intact and prevent the player from having actual misgivings about the whole project! so let's quickly introduce the fake cheesy german accents, the secret society of Jewish super-science, and mecha-Hitler! The result is a world in which only the Good Guys are allowed to have an inner life, while the Bad Guys are mere cardboard figures to be mowed down by the player's avatar's inhuman knife skills. It's... galling, and surprisingly more fascistic than the creators probably intended.

Great takes, and makes me think back to the Zone of Interest - the perfectly bathetic tonic to Wolfenstein and Schindler's List blowing it all up.