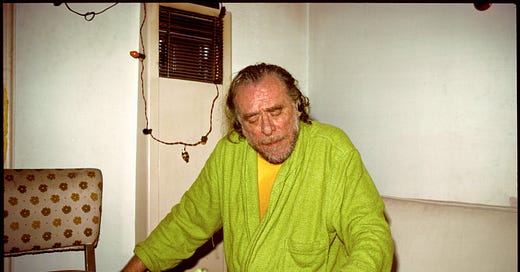

Must we burn Bukowski?

Is the misanthropic "poet laureate of LA lowlife" one for the dustbin, or can he teach us something about feeling?

“Charles Bukowski” was a very successful character played by Henry Charles Bukowski for some time. This character was largely based on the fictional Henry Chinaski, the protagonist of Bukowski’s novels, even though much of the poetry attributed to this similarly fictional person predates said novels.1 After Henry Bukowski’s death, the character of “Charles Bukowski” was undertaken by Henry’s publisher John Martin, and several of Henry’s poems are allegedly more Martin’s work than Henry’s. I suppose Martin has about as much right to be “Charles Bukowski” as Henry did, considering neither of them were actually “Charles Bukowski” in the first place.

The character of “Charles Bukowski” is a masterly impersonation of a concept, a popular ideal of a “20th-century poet.” Arrogant, dour, drunk, self-destructive, and masculine, this “Bukowski” appeals largely to people who don’t read much poetry. He appealed to me as a young person who didn’t read much poetry, and I wrote a lot of awful “poetry” inspired by “Bukowski.” He’s a lot like Rupi Kaur in that way (they both even do the ostentatious “all lower-case letters” thing, although Bukowski at least had the good sense to not overdo it and capitalizes his “I,” though not the good sense to stop him from doing it to his titles), albeit Kaur comes off a lot less like an asshole.

I remember my first day in my first creative writing workshop in undergrad telling the class during our introductions that my favourite poet was Charles Bukowski and receiving more than a few smirking side-eyes. Pretty soon I started to feel shameful about this opinion, and over time the Bukowski poems I’d pinned to my walls started to make me cringe and were replaced by excerpts from a class of more refined edgelords, people like Fred Seidel, Billy Childish, and Kathy Acker. Bukowski’s performance became more and more obvious and hysterical to me the older I got and his clownish antics more and more pathetic and embarrassing—I hazily remember some recording of a reading he did where he throws a tantrum because he hasn’t been provided enough booze on stage. I scrubbed all reverence for Bukowski out of my life—so did all my other similarly-aged friends2—and developed my own smirking side-eye toward those guileless sons of bitches who might cop to their own devotion to the man. How banal. How gauche.

Years passed and one night I was introduced to the work of Daniel Jones by a friend (Discordia’s own Sire) leaving me one of his poems as a drunken message on my answering machine. I quickly fell in love with Jones’ work, particularly his collection The Brave Never Write Poetry, finding it extremely exciting and refreshing in its unabashed, unguarded rawness—and was left thinking of Bukowski, an obvious influence on Jones. Then COVID hit, and, like many of you, I spiralled through a series of bored existential crises (which eventually culminated in me entering law school, a tragic misstep I don’t recommend), with one of these crises convincing me to revisit the favourite poet of my youth and pick up a copy of Pleasures of the Damned—and I genuinely felt caught off guard by the work, in spite of the fact that I could still recite a lot of “empire of coins” from memory.

There are a couple of things to admire about the “poet laureate of LA lowlife.” He never went through an MFA program, for starters. He never taught at one either. There’s something quintessentially outsider about his work that I think resonates with me more now, now that I’m more thoroughly steeped in poetry, than it did when I was first reading Bukowski and didn’t possess the palette to appreciate that particular flavour. In spite of how transparently Bukowski is making a caricature of himself (anyone who has read through his letters can attest to how embarrassingly cloying and deferential they are for a man who made his name as being a supposed “badass” who could care less about what other people think), there’s a lot of raw, exposed nerve on display here, Bukowski leaves himself open on the page in a way not many poets are bold enough to. That said, certain moments that gripped me as a young reader feel juvenile now. “Believability” is an issue. I remember watching a documentary some time ago called Bad Writing in which a bad writer is instructed that the problem with the angst in his poetry is that it “isn’t believable,” that a reader couldn’t possibly believe your pain is “that” bad, that you need to sell a reader on your pain before expressing it that melodramatically. I learned this more thoroughly in my aforementioned first year of creative writing education—and hey, maybe that’s the problem. Maybe for all my own “outsider” pretensions I’m too much of an institutional worm now, and my proximity to raw and unfiltered human emotion is cautioned by an “academic’s” repressive approach. Maybe I’m the problem and not Hank.

I’m pretty miserable these days, and perhaps there’s something sad about the fact that I can’t connect with someone being so expressively miserable himself, that I cast the same doubts on “Bukowski” that I do on myself. Self-pity is different when you're a teenager, or when you’re “Bukowski”; it’s purer. I was talking with a teenager the other day and they told me “I wish I was dead,” and even though I sometimes have the same feeling—don’t we all from time to time?—I didn’t say anything because my self-consciousness about my misery is something which now eclipses my own misery itself. For a lot of people, that’s just part of growing up. Re-reading Bukowski, I began to wonder: is that such a good thing?3

if it doesn’t come bursting out of you

in spite of everything,

don’t do it.

unless it comes unasked out of your

heart and your mind and your mouth

and your gut,

don’t do it.—Charles Bukowski, “So You Want to Be a Writer”

LIKED THAT? MAYBE YOU’LL LIKE THIS

Chuck Palahniuk and the Gay Nazi

It’s always one Chuck or both. Palahniuk and/or Bukowski. The reason is obvious: these guys are in-your-face and your parents probably wouldn’t approve of the things they describe or opine, and so their fan bases have a tendency to skew toward your more gormless edgelords, the kinds who can only really identify “counterculture” in the most obviously ant…

Bukowski actually refers to himself in several of his poems as “Mr. Chinaski,” for what it’s worth.

Here’s an aside for you: in spite of the stereotype of the typical Bukowski reader, most of the big Bukowski fans I’ve known in my life (including all of the friends I’m referring to here) have been women. A friend who teaches creative writing (and who was actually my first cw prof in that aforementioned class) once confirmed this observation herself, telling me that the lion’s share of positive comments she’s heard in class from undergraduates about Bukowski’s work have come from young women, something she felt a little concerned by as the man’s work is undoubtedly, unabashedly, unironically misogynistic. By the end of this piece I will reassess some of my feelings about Bukowski, but make no mistake, as most people already know, this is writing that betrays a deep personal contempt for not only most other people (it’s obviously very misanthropic in general) but specifically women. One may argue that this element of his work may help explore the roots of these frustrations in the psyche, but that’s for you all to decide on yourselves.

Another aside, an addendum really: to be fair to Hank here, he wasn’t unaware of his own ironies, and had a lot more sense of humour about himself than I think his more guileless fans tend to realize (I certainly didn’t realize it as a teenager and took him painfully seriously). Take this excerpt from “about pain”:

my first and only wife

painted

and she talked to me

about it:

“it’s all so painful

for me, each stroke is

pain…

one mistake and

the whole painting is

ruined…

you will never understand the

pain…”“look, baby,” I

said, “why doncha do something easy—

something ya like ta

do?”

about the best you could do as a very pockmarked, closeted gay man facing early deindustrialization

I'm embarrassed by these writers who became clowns so people would pay attention to them. Remember when James Ellroy made a complete fuckin' fool of himself on the Conan O'Brien show, jumping around and making funny voices? And that "I Hope They Serve Beer In Hell" guy - What did you expect to happen? And that Michael O'Donahue fool . . .