When Adolf Hitler wrote science fiction

On Norman Spinrad's 'The Iron Dream' and the ideology of our escapism

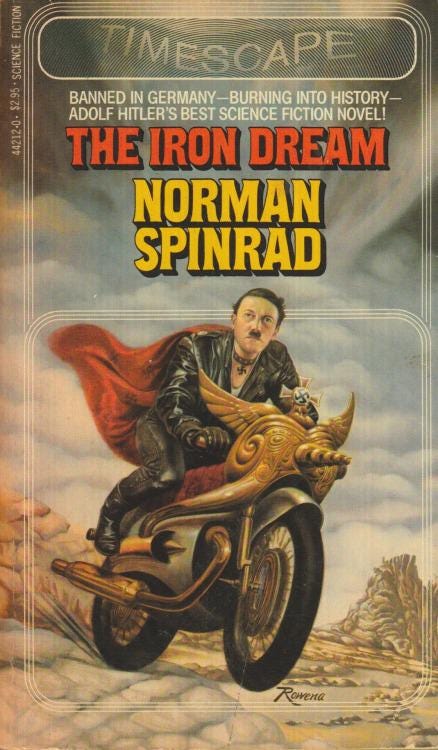

Imagine going into a bookstore in the 1970s or ‘80s and venturing into its back-of-the-store science fiction ghetto. Your senses are assaulted by the products of the unquestionable peak of sci-fi cover art, in all its gaudy and brightly-coloured glory—depictions of chrome machines with those classic spots of airbrushed white lustre, austere space stations lording menacingly over mist-frosted planets, epic and nearly-nude Frazetta-esque melodramas playing out atop craggy peaks, and acid-washed alien psychedelia imposed on gradients of garish Day-Glo-like pigments. Then, imagine, in the midst of it all, seeing this:

Adolf Hitler, dressed up in Judas-Priest-esque leathers, riding a golden-winged motorcycle through an alien wasteland, as his heroic red cape flutters behind him in the wind. It would be impossible to not feel at the very least compelled to pick it up. And after reading the back matter, I can’t imagine not feeling compelled to open it too. Norman Spinrad’s The Iron Dream contains the complete text of Lord of the Swastika, a novel written by an alternate-historical Adolf Hitler who emigrated to the United States, and, after working for years as a science fiction cover artist, became a science fiction novelist too.

The book’s true author, Norman Spinrad, is a strange and fascinating literary figure. He was responsible for writing “The Doomsday Machine,” one of the all-time most beloved episodes of the original Star Trek, but the actual books written by Spinrad, a self-described anarchist, often drift into more critical and sometimes downright surreal fare. His novel A World Between imagines a literalized “war of the sexes” between militant lesbian separatists and chauvinistic traditionalists. The deceptively-normal title The Void Captain’s Tale masks a story about faster-than-light travel being powered by psychics who cum (not an exaggeration for effect). The explicit sex in his William-S.-Burroughs-esque proto-cyberpunk Bug Jack Barron, serialized in New Worlds, got him personally denounced by British parliament, treatment that even his fellow New Worlds contributer J.G. Ballard never received. This is a man who inspired French space rock epics on albums featuring spoken-word sections by Deleuze. This is the work of a man who might not merely write about outer space but in fact actually be from there too.

Spinrad viewed traditional escapist science fiction and fantasy with a great deal of suspicion. “There is something deeply disturbing in the congruence between the commercial pulp action-adventure formula and the Übermensch in jackboots,” he wrote in his essay collection Science Fiction in the Real World. In The Iron Dream’s novel-within-a-novel, Lord of the Swastika, Hitler’s Feric Jagger is a hero by birthright, empowered by his pure genes as much as Aragorn is by his Dúnedain heritage or Luke is by his hereditary force-sensitivity. Per Spinrad’s description, Jagger “fights his gory way from ignominious exile in the lands of the mutants and mongrels to absolute rule in the Fatherland of Truemen, after which he wages a successful holy war to purge the Earth of degenerate mutants and sends off clones of himself to conquer the stars.” The horrifying thing about Hitler’s novel is that by abstracting his subject, by approaching it with substitutions, with euphemisms, you find it easy to root for Feric, even though you are consciously aware of what the work is presenting an allegory for. Despite knowing what the book is doing, you can’t help but want Feric to succeed: it’s what the conventions of the genre demand. You begin to feel the same frustrations Feric has with the “Deceivers”—obvious Semitic stand-ins—and feel the impulse to cheer when he overcomes them, because Spinrad plays so well into these conventions. It’s a deeply disturbing reading experience. As Le Guin put it, “the tension and discomfort thus set up may prove salutary to people who are used to swallowing the stuff whole.”

It is the same tools at play in Lord of the Swastika that undergird so much of the media we so passively consume, which subconsciously reinforces the dominant ideology, the dominant status quo, by using genre conventions to exploit our natural identification with them. You root for Wakanda to protect the imperialist West from the exploited revolutionaries, whether they be from Black America (in the first film) or the “Global South” (its sequel), with help from characters representing the CIA. How easy does it then become to substitute the pantomime villain in the juvenile charade that is the Marvel movie with a real man like Ibrahim Traoré in Burkina Faso? For all their liberal sentiments, the natural exceptionalism of these blockbuster heroes is no different from the nativist pretensions of the MAGA-hatted Trump supporter. “The identification figure isn’t just a sympathetic hero, he’s the ultimate wank fantasy,” writes Spinrad, “the reader as rightful Emperor of the Universe, indeed as the Godhead. The stakes are nothing less than human destiny for all time, and the Princess to win is always the number one piece of ass in the galaxy.” It’s no wonder that Elon Musk, that Special Boy, that one-time liberal superhero—in fact, he inspired the cinematic version of Iron Man—eventually revealed the fascist psychopath beneath that smirking technocrat exterior. They all come from the same blueprints as Feric Jagger.

Like much of the world’s best satire, the book’s poignancy is enhanced by just how many people don’t get the joke. Neo-Nazis lapped the thing up like it was The Turner Diaries and added it to their recommended reading lists. Some fans, according to Spinrad, even complained that they were really engaged by the story and felt bitter about having it all presented in the Hitler frame. This all goes a long way to proving Spinrad’s own point, which he writes with sneering emphasis: “the Emperor of Everything really is Der Führer, suckers, and you have been marching right along behind him.”1

P.S. What is Spinrad up to today? He remains weird and keeps his activities diverse. He’s a man who writes both screenplays for historical films about the Gauls and also bizarre self-published novels about a successful post-al-Qaeda Caliphate while sometimes randomly showing up to serenade audiences at the circus with his Lou Reed croon. Oh yes, and he’s also occasionally on YouTube making these videos that

dug up:Hope you enjoyed this quick piece while we get ready for our next event in Montreal at the legendary DIY venue previously known as Traxide, now known as Thrashcan. See the details here.

I do have some qualms with the book’s framing depiction of the USSR that I think ironically plays into some Cold War anxieties that a lot of genre fiction did a lot to reinforce as well—though of course the novel is primarily focused on more ancient “universal”/Campbellian stuff than say the mere contemporary ideology I alluded to with my Marvel critiques above.

Norman got very Into YouTube in 2007 or so, and there's a treasure trove on his channel of the dude just kind of amusing himself doing goofy, very un-PC dad jokes. Funny or Die really missed the boat on this guy.

The idea that Norman Spinrad is still alive is wild!