"[Vuong begins to cry]": The war on Ocean Vuong

How shifting cultural currents and media oversaturation will bring a bookshelf behemoth to his knees

The Vibe Shift has come cataclysmically for Ocean Vuong. Really, he should have seen it coming. On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous was an extremely pre-Vibe-Shift book—a queer POC diaspora novel about intergenerational trauma? Christ, Penguin’s data-crunching computers must have been sputtering smoke and lighting up like fucking Times Square when they saw that one! Of course they picked it up, and of course it sold like Vietnamese banh xeo,1 moving over a million copies and being translated into forty languages. It seemed like every straight woman and tenderqueer I knew owned a copy of the thing, and eventually a copy wound up in my apartment—wasn’t for me. I mean, the title alone put me off, because it’s just so fucking poncy, and the book itself was as much of an overwritten mess as that title would suggest, filled with empty-headed philosophizing. I put it down after maybe a couple dozen pages and then never picked it up again. The critics, on the whole, seemed to lap the stupid thing up.

Then it came time for Ocean Vuong’s second novel, The Emperor of Gladness. While still skeptical of Vuong as a thinker, Andrea Long Chu (the It Girl of the Trans World) saw Gladness as a great step forward for him as a prose writer. A week later, motherfucking

himself wrote in The Guardian calling it “heartbreaking, heartwarming yet unsentimental, and savagely comic all at the same time.” Maureen Corrigan on NPR simply called it a “truly great novel” and then later that same paragraph additionally a “wonderful novel.” Max Liu, on the other hand, writing for Financial Times, called the execution “clumsy” and riddled with depictions that “ring false.” A little while later the Times Literary Supplement’s Claire Lowdon, who had excused the excesses of Gorgeous as a consequence of an “exciting talent try[ing] things out on the page,” was unforgiving: “I have no idea whether Vuong’s new novel was difficult to write. It was definitely difficult to read.” Critical consensus seemed unattainable on just about every part of the book: the alleged “vividness” of Vuong’s descriptive capacities was written off as purple prose; the humour Harrison described as “savagely comic,” Lowdon called “crude, cartoonish or just a bit limp”; even Chu’s simple celebration of the book for “having a plot” came up against Liu’s claim that the book had “little plot” to speak of at all. But none of this growing backlash could compare to what was to come. The arrival of the apex bitch. I am of course talking about Tom Crewe’s now infamous piece in the London Review of Books.Crewe’s piece will probably go down in history as a turning point in the discourse surrounding Vuong. The London Review of Books doesn’t pull its punches as much as some of the other guys, but this was ruthless, and I suspect that, coupled with Vuong’s oversaturation via his abundance of media appearances—the press tour Penguin has organized for Emperor has been massive2—the situation will further deteriorate from here. Yes, a lot of those aforementioned reviews were still positive, but we should note:

The negative press started after the good press, which was early and likely included all the people who received ARCs specifically because Penguin expected them to hype the book up, and the press has only been getting more negative. This looks to me like it has the possible trajectory of a snowball; and

As we have discussed on this blog before, literary media has grown unbearably soft, and it is becoming more difficult to overcome an outlet’s resistance to publishing anything unabashedly negative.

I set out wanting almost to defend Vuong from his haters—yes, his novels wipe the dog’s ass, but his poetry is at least somewhat competent,3 and hell, isn’t it a good thing that someone with real “literary” aspirations is in the public eye and being interviewed by GQ? Like, who else have we got? On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous and The Emperor of Gladness have people en masse reading novels that aren’t just Harry Potter or some Harry Potter derivative slop where the Harry Potter stand-in characters have steamy fuck sessions! In the spirit of Mark Fisher I’m made to ask—is there a literary vampire castle? Can anyone appeal to as large an audience as Vuong without pushback? Like, Christ, he’s not fucking Rupi Kaur for God’s sake. Whether I think Vuong’s work is sort of shitty seems beside the point, because we are fighting a losing battle here to keep literature relevant, and we are on the verge of publicly burning one of our most prominent voices at the stake—as that GQ article suggests, Ocean Vuong may very well be “the last celebrity writer.” Madonna isn’t exactly writing blurbs on the jackets of books by Lucy Ellmann. I say all this, but then I can’t ignore the things that actually come out of Vuong’s mouth, which reveal that the man isn’t really an influence I’d like on a burgeoning literature-reading renaissance, for the simple reason that the man is a fucking illiterate bellend.

Crewe points out that Vuong talks about writing a “poetic novel” as if he’s the first to ever do it, as if he has no idea that modernism ever happened. But basically everything Vuong says suggests a total ignorance of the medium in which he’s working. Describing some of his white students, he says they tell him:

‘I am white, I am male, but I want to write a new kind of novel that considers the people and the concerns of the global world and power dynamics that I understand in my classroom,’… I tell them, ‘I'm sorry that you do not have good white models to do what you want to do, so you will now have to be the first.

…The first? Vuong, have you never heard of J.M. Coetzee? He won a fucking Nobel Prize for doing just that. What about E.M. Forster? Mark Twain? Alan Paton? John Steinbeck? Herman Melville? How about William Faulkner? I know Vuong has heard of William Faulkner,4 because he goes so far as to mention him by name:

I have earnest white men who are my students who want to be politically aware. They are very diligent about trying to enter a new era for themselves. And meanwhile, the white canonical writers have failed them in political consciousness—you don't turn to Faulkner or Hemingway to have an equal rendering of Black characters, right? Those are not good examples of it. And so, in a way, the canon failed them in their current ambitions to be ethical and capacious in how they see the world in their work.

If you think that Faulkner fails white readers with regard to political consciousness of black station in America, just admit you haven’t fucking read him. Yes, obviously a black writer will approach these sorts of subjects with a different hand, but I don’t see how you can look at books like The Sound and the Fury or especially Go Down, Moses and not understand the value the works pose for understanding the racial tensions of the post-reconstruction American South. I think that Faulkner’s exploration of American race relations is easily as valuable to a reader as Baldwin’s. But here’s the thing: if you’re looking to literature principally as a means of opening up your “political consciousness” then put down the Colson Whitehead or whatever it is you’re reading and read some Marx, read some Nkrumah, read some Fanon, or even just read some of Baldwin’s essays rather than his fiction. If you think you can get a real sense of “political consciousness” from fiction then you’re plainly digging around in the wrong dirt. The other thing is that Vuong’s students go to NYU. I found a syllabus for an NYU Intro to English course online, and while, yes, they read Ernest Hemingway (…why shouldn’t they?), they also read Gwendolyn Brooks, Benjamin Zephaniah, Li-Young Lee, Alice Walker, Nana Kwame Adjei-Brenyah, Octavia Butler, and Shaun Tan. There is not a dearth of diverse literature being taught at NYU. If these kids are asking Vuong for it then they’re plainly not doing their course readings. I wonder whether Vuong has made these kids up entirely, or if he’s just projecting out an image of his average reader, an archetype that also happens to be swiftly dying out.

5 Vuong’s content is idpol slop, cheap ammunition in the culture war that once was. I don’t think his work would have gotten as far as it did without some serious help from the Penguin marketing department. The book was sold as precious “Voice Uplift.”6 It was exactly what Vuong’s (alleged) well-intentioned but wrong-headed, white-guilt-riddled students were looking for: a text you don’t necessarily read for its aesthetic qualities but because it will work to purify your soul of racism or whatever. You read it as sacrament, you read it because what matters is condescendingly “listening to voices.” The other principal demographic for this shit outside of self-flagellating whiteys is bougie POCs who secretly don’t feel “POC” enough because of the “bougie” part, because they have come to fetishize suffering as an integral part of being a “POC.” Since they themselves hardly ever suffer, they get vicarious kicks by reading about other less fortunate non-whites suffering. In both cases the belief is that imbibing this stuff can transmute one’s self into moral gold, entering an enlightened state and helping transform this world into a more tolerant one.

The second election of Donald Trump (which we assessed in-depth here), something that all the “Voice Uplift” in the world wasn’t able to stop, made all that shit instantly seem trivial, and what’s more is that the much-publicized support for Trump among some “POC” communities and the lack of support for Kamala from black men (though I think expecting black men to vote for a former DA is some next-level insult) exposed sheltered whites to the novel conception that minority communities are pluralistic. This means that not only is identity politics politically useless, “Voice Uplift” is even less than useless because, surprise surprise, no one subjective experience can stand in for the complexities within a group. In fact, Vietnamese people in particular, Vuong’s demographic, are stalwart Republican voters and always have been, so listening to Vuong will in no way “enlighten” you about a community Vuong stands apart from. And so, you’re left with the question: if there’s no political value to reading Vuong’s novels, if the simple act of reading them will not magically make me understand his community and be able to solve racism, then what value is there? This is a major essence of the so-called “Vibe Shift” and it will greatly devalue what capital Vuong’s work has, and if Vuong is desperate enough to retain his relevancy then I guess he’ll have to cynically up and move to Dimes Square and become racist, or just “apolitical” (read: racist).

Crewe was not exaggerating when he took aim at Vuong’s writing and he was not cherry-picking—it’s just that bad. I opened to one random page of Gorgeous and had a hard time choosing between “When you say Trevor you mean the action” and (describing his beau not wanting to eat veal) “Trevor who would never eat a child,” only for my eyes to venture to the next page and see this Trevor described as “skull-thin,” evidently an attempt by Vuong to avoid the cliché of “skeletal” only to choose one of the wider bones. It’s imprecise, clumsy, silly, overwrought. Every circumstance which befalls Vuong’s author insert character, every action, is rendered with such unnecessary weightiness. It never stops. Like, here’s Ocean Vuong drinking milk:

I’m drinking light, I thought. I’m filling myself with light. The milk would erase all the dark inside me with a flood of brightness.

And here’s a quote from a story that I wrote when I was eighteen:

By the break of day I am found digging golden dandelions from between the sheets; the seeds that sowed while we slumbered, that now threaten to set my linens ablaze in their golden fury.

Wow, pretty heavy description of making the fucking bed. A lot of young writers have this problem—not being able to step back and recognize when their prose is simply becoming self-serving and pompous. You can see in my juvenile writing that I was extremely impressed with myself for comparing sunlight falling onto a bed with dandelions, and the way I’m wielding it is overwhelmingly insistent and smug. But you learn. Or you’re supposed to, anyways. Noticing that two things are yellow (the sun and dandelions) is not a brilliant observation you need to jerk off too hard—likewise noticing that two things are white (milk and light). But Vuong was 30-years-old when he wrote that. That same year he also wrote this: “No homo, he had said. But all I heard, all I still hear, is No human.” I don’t know if even at eighteen I’d have been dumb enough to write that as the capstone for a piece, yet there it is in the fucking Paris Review!

In one interview, it becomes clear that Vuong believes the very stupid myth that glass is actually just a very viscous liquid7: “that’s what language is: the glass. You think it’s fixed. You think it’s clear pane of glass. But in fact, through years, it starts to drip and melt and change.” He says all of this as part of a diatribe about how it’s racist to standardize language, because it hasn’t occurred to Vuong that “standardization” did not principally happen as a means of creating cruel normative standards, but because it is efficient for governance and the administering of social services—it is generally a good thing if most people living in a country can ascertain what one another means with high certainty, because if you speak a dialect your doctor in the ER can’t, that could kill you—language is not merely expressive, it’s ideally supposed to be communicative too. That being said, I wouldn’t be surprised if Ocean Vuong’s words could get him killed in an emergency because he uses words to mean basically whatever he wants. Take, for instance, Vuong discussing his past relationship with his partner’s Lithuanian grandmother: “here I am, a Vietnamese refugee living with a Lithuanian refugee, from two different American wars…” What the fuck is Vuong trying to imply? That, like Vietnam, the Second World War was a war of American aggression and that they are both victims of the Americans? But to even call the Second World War an American war? It was a world war, you fucking dunce! It’s there in the mother fucking name! The Americans weren’t even in Lithuania!8 As for war refugee, Vuong isn’t a war refugee in the sense of someone who literally lived through a war, he left Vietnam in the late 80s because of the US’s Amerasian Homecoming Act.

And don’t get me started on just how fucking bizarre his interview appearances are. When he’s not simply free associating, he seems to be doing continuous emotional somersaults, engaging in histrionics that I’d say either seem staged or like someone needs a higher dose of lithium. Take this excerpt from a New York Times interview he did in May of this year:

When I was 15, I decided to kill somebody.

Oh, my God.

I didn’t do it. Ah, my God. [Long pause.] I was working on the tobacco farm, and I rode my bike every day. It was five miles out. You wake up at 6 in the morning. I rode my bike, and I went to work mostly with migrant farmers. You’d get paid under the table, and if you show up every day, you get a $1,000 bonus at the end of the season. It was this hot July evening. I was in my room and I look out the window and see that someone has stolen my bike. It was someone I knew in our neighborhood. He was a drug dealer. You would put your bike outside on the stoop when you’re running in and out, and this guy was known to grab your bike, and there’s nothing you could do about it. But I snapped that day. I saw him, and I was so angry, because I knew: I’m not going to get this back, I’m going to lose my $1,000. For context: My mom made $13,000. I go outside and say, “Give me back my bike.” And essentially he said, “Eff off.” I lost it. I went across the street to my friend Big Joe’s house. I knocked on his window. I remember putting both of my hands on the windowsill. I have no shirt on. I’m sweating, I’m so angry, and I said, “Please let me borrow your gun.” [Vuong begins to cry.] I’m so sorry.

Can I give you a hug? [Vuong and I embrace.] I appreciate that you’re being honest, but if it’s too much, we can stop. OK?

I think what I’m trying to get at is that I didn’t become an author to have a photo in the back of a book.

I used the phrase “intellectual himbo” when I profiled Simon Wu a while ago, and I think that Vuong very much fits the same shoes. In fact, Vuong and Wu have a lot of identity tag overlap—well, okay, namely they’re just both gay Asian guys, but they also have this hilariously nonsensical way of approaching profundity that sits somewhere between Zoolander and Xavier: Renegade Angel. They plainly do not understand philosophy, and so they think that to be philosophical is simply to speak nonsense. Vuong asks such empty-headed free-associative bullshit as “what is a country but a borderless sentence, a life? …what is a country but a life sentence?” which pairs nicely with the sorts of rhetorical queries Wu poses, such as “if gays don’t make babies when we have sex what do we make?” and “what is gay or straight when you’re a tree?”

But Wu does at least put it very aptly and succinctly when he says that, in this day and age, “the personal is political is profitable.” And, as I’ve established, that’s the crux of Vuong’s whole grift, whether he’s aware of it or not. His continuing profit is dependent on a projection of a politic that his person exudes. Or is supposed to.

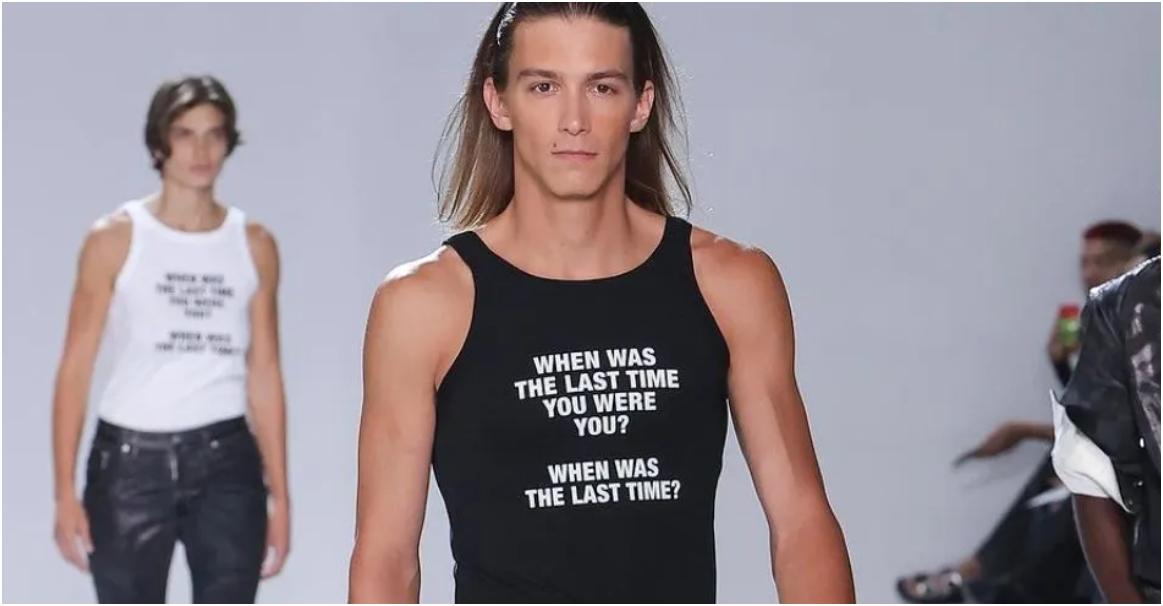

The problem is that Vuong can’t keep it up and likely won’t. His “politic” is too utterly compromised, because he’s too smooth-brained to at least make the grift seem coherent. Vuong talks so much about “the working class” and he writes these books about “working class” anguish that make Jacobin writers swoon, and yet he’ll turn around and collaborate with Helmut Lang on New York Fashion Week runways.

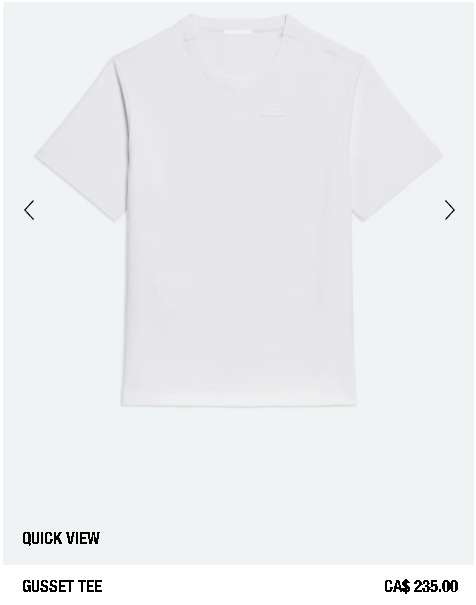

You know, Helmut Lang, where you can go and buy this $235 white t-shirt.

You know, Helmut Lang, a subsidiary of Prada, a company whose supply chains, among other things, may involve slave labour, a fact about which Prada simply doesn’t seem to give a shit.

, in the aforementioned Jacobin piece, writes about how Vuong “[found] a way to ‘get out’ of poverty and precarity, without forgetting what both mean for millions of our fellow Americans,” but where exactly is that visible here? What does this collaboration do other than show Vuong’s willingness to actually just totally forget what “poverty and precarity” mean if it means he gets to put his writing on a stupid fucking t-shirt at New York Fashion Week? Respect the drip!!!The times are changing too rapidly for Vuong to keep up and he can barely keep himself coherent as it is. He will stumble and contradictions will spill out of his pockets like cold spaghetti. He lacks the ability to truly understand what is going on around him. Here’s a quote from On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous, from far further into the book than I ever made it, that Crewe excerpted to make a point about the way Vuong makes every scene in his books “bloated with rhetoric,” though I will use it to demonstrate something else:

I’m thinking now of Duchamp, his infamous ‘sculpture’. How by turning a urinal, an object of stable and permanent utility, upside down, he radicalised its reception. By further naming it Fountain, he divested the object of its intended identity, rendering it with an unrecognisable new form.

I hate him for this.

I hate how he proved that the entire existence of a thing could be changed simply by flipping it over, revealing a new angle to its name, an act completed by nothing else but gravity, the very force that traps us on this earth.

Mostly I hate him because he was right.

Because that’s what was happening to Lan. The cancer had refigured not only her features, but the trajectory of her being. Lan, turned over, would be dust the way even the word dying is nothing like the word dead. Before Lan’s illness, I found this act of malleability to be beautiful, that an object or person, once upturned, becomes more than its once-singular self. This agency for evolution, which once made me proud to be the queer yellow faggot that I was and am, now betrays me.

This is not only extremely insipid writing, it is also just plain incorrect. That is not even remotely what Marcel Duchamp was doing. In fact it’s the opposite. The point of Duchamp’s Fountain is that it is not the urinal which has principally changed, it is the context which has changed—it has been placed in an art gallery context. What Fountain interrogates is what authority determines what is or is not art. The signature on the piece, another detail Vuong ignores, exists to demonstrate the presence of an auteur asserting it as an original work, and its inclusion in the gallery suggests the concurrence of the curatorial authority: it has been accepted, here it is, it is art. It is context which has truly been inverted, not the object-in-itself, and that is what changes everything. The turning of an object is incidental in the face of the turning of context. And now, as those mercurial Vibes ever Shift, we all sit and watch as all context turns around us yet again, perhaps we even bear witness to an apocalyptic Fourth Turning if you’re a reactionary dipshit. Ocean Vuong won’t survive this one simply by standing on his head.

P.S. Uhhh thanks to everyone who pointed out that I’ve evidently been using “nonce” incorrectly for the past twenty years (North ‘Murican), I’ve amended that. Not trying to accuse him of uhhhhhhhh… that.

LIKE THAT? MAYBE YOU’LL LIKE…

What the fuck is "Asian American-core"?

Is Simon Wu one of the dumbest essayists alive? Read about his vacuous thoughts on fashion and his inability to understand Marxism.

It’s a kind of Vietnamese pancake. Therefore a “selling like hot cakes” joke. Geddit?

This year alone so far he has appeared in PBS NewsHour, NPR’s Fresh Air, NBC News, The Guardian, BOMB, Esquire, The New York Times (twice), even the fucking Late Show and Late Night. In each of these he comes off like a used car salesman of the soul.

I recently flipped through his latest poetry collection, Time is a Mother, and found some fine turns—the description of “kerosene-blue eyes" was very evocative, and imagining the smoke bellowing from a pet crematorium as “little poodles” in the sky was both funny and poignant, a juxtaposition which tends to be all I’m looking for in a good poem, though quite a bit of it was just empty aesthete nothings like polished marbles. Ironically, much of it would make far better prose than much of what he passes off for prose in his novels.

Oh, and he shouts out Lil Peep, and I quite like Lil Peep. Last year I had some correspondence with Peep’s grandfather, the Marxist historian John Womack, which was very pleasant.

Vuong does talk about Melville in another interview, for the record, and seems to like him. He even mentions in passing that Moby-Dick deals with race in America, so this seems to confirm my suspicion about Vuong which is that anything is true insofar as he wants to say it in a given moment, which, as a blogger, I empathize with. Anyways, if you’ve been holding out on reading Moby-Dick, don’t worry, in the same interview Vuong let’s us all know he “still think it holds up as an American masterpiece.” Thanks, Ocean. I was worried for a minute there.

[EDIT] Holy shit, this was a fucking throwaway caption gag about Oprah, calm down you fucking spazzlords.

I don’t think this is the sole reason he’s popular for the record—I don’t think the aforementioned positive reviewers like him because he’s “Voice Uplift”—but the keywordicism is a big part of his appeal for a lot of people, and why Penguin has pushed his work so hard, that’s what the lit market is geared for.

That grandmother, Grazina Verselis, is the basis for a character in Vuong’s latest novel, The Emperor of Gladness, also called Grazina. Vuong’s fictionalized depiction of his relationship with Grazina is troubling for all that it reveals about Vuong’s ignorance about what exactly happened in the Second World War. Many of the fictional Grazina’s comments are plainly inaccurate, either the result of poorly-researched original dialogue or just the reproduction of lies that Vuong was actually told, likely as the real life Grazina was trying to mitigate potential understanding of “what side” she was on during the war. For instance, Grazina says: “the Nazis would bomb anything, even water.” The Nazis barely touched Lithuania with bombs after their initial push in 1941. Vuong also communicated the fictional Grazina telling him:

The Red Army, after pushing back the Nazis, invaded Lithuania in June of ’44... Two weeks before Vilnius was occupied, her father took her and her brother onto a train heading west into Germany, where they would hopefully sneak into occupied France, then perhaps London. Though the Germans might have had plans to exterminate them eventually, the Communists posed a more immediate threat...

The fact that Grazina’s father feared the Soviets, whose government he would have already lived under, so much more than the Nazis, enough to try escape into Nazi Germany in 1944 (almost sounds like they actually fled with the Nazis) rather than try his luck remaining in Lithuania, all but suggests that, if this is in any way based on the real story of Grazina Verselis, Grazina’s father was a Nazi collaborator. Why else would he suspect that there was something to fear when the Soviets came back into power? What did Grazina’s father do that would mark him specifically as being in danger? That makes sense when we then consider the story about how (according to Vuong’s retelling) Grazina’s father’s business was the only one on his street to not have the windows smashed up by the invading Germans. The real Grazina Verselis was born in 1925. She would have been twenty when the war was over, too old to have not known what was going on. The fictionalized Grazina even had a husband who fought in Lithuania, who her son in the novel describes as “a soldier in the resistance. He fought against Stalin and the Nazis.” Bullshit. Even though the Nazis opposed Lithuanian independence, the Lithuanian resistance collaborated significantly with the Nazis, especially in the persecution and killings of communists and Jews. If this story was also one that Vuong was told, then, once again, he was duped by a guilty Nazi.

I read this review in dialogue with Tom Crewe’s review in the London Review of Books, which provided plenty of concrete examples abt the quality of the prose. This review appears to expand, or contextualize, that criticism in terms of the current political and cultural moment. The negative comments here don’t seem to realize this context, and feel that it’s a random ad hominem attack on Vuong himself.

I really, really distrust these moments when everyone turns on a writer at the same time