Who chained hundreds of metal books to Toronto street posts?

And why were they all defaced in a single night? The secret of one of the world's great street artists.

This article was originally written and published as “Rocky Dobey: ALL THAT IS SOLID” in issue 2 of Souvenir zine (2018). The text has been lightly updated, and a brief epilogue appended. For the extra curious, I’ve also created a separate post here with a map of where some of these pieces can be found in Toronto. Photos unless otherwise noted are my own.

Not too long ago I read an article about aphantasia, or “imagination blindness.” Aphantasics are unable to picture things in their heads. While I don’t have the condition, my visual imagination is a bit weaker than the average—I can, at most, hold a flickering image of a familiar face in my mind’s eye for a moment or two before I lose it. It’s no doubt part of the reason I get lost easily, and why I’m regularly thunderstruck by features of my own home, like the Dairy Farmers of Canada calendar that hung invisibly (to me) on my fridge for almost a year before one day I just kind of re-noticed it there and changed the month from January to November.

I’d like to think that in a strange way this defect helps to keep me curious. Although my mental map of Toronto dissolves into incoherence as I walk, its details remain perpetually new to me, particularly the street poles, textured with scrapyards of rusted staples, posters, stickers, paint and, here and there, weathered copper plates bolted into the wood. These last fascinate me most. Near College and Spadina, you can find a few baffling plates that can be rotated by hand, though the objects that were once mounted to them for display have long since disappeared. On a pole at the southeast corner of College and Bathurst, a metal letter H is going penny-green under traces of cobalt blue paint and etchings that recall the fine-boned skeletons of fish. On a Kensington sidestreet, a peculiar ball of mulched bookpaper and rust. One post sheltered by the Church of St. Stephen-in-the-Fields yields many finds: a rough-looking plaque, dated 1995, memorializes murdered Indigenous activist Dudley George; another, from 2000, depicts a ragged, burning heart surrounded by cryptic phrases and the command to REMEMBER.

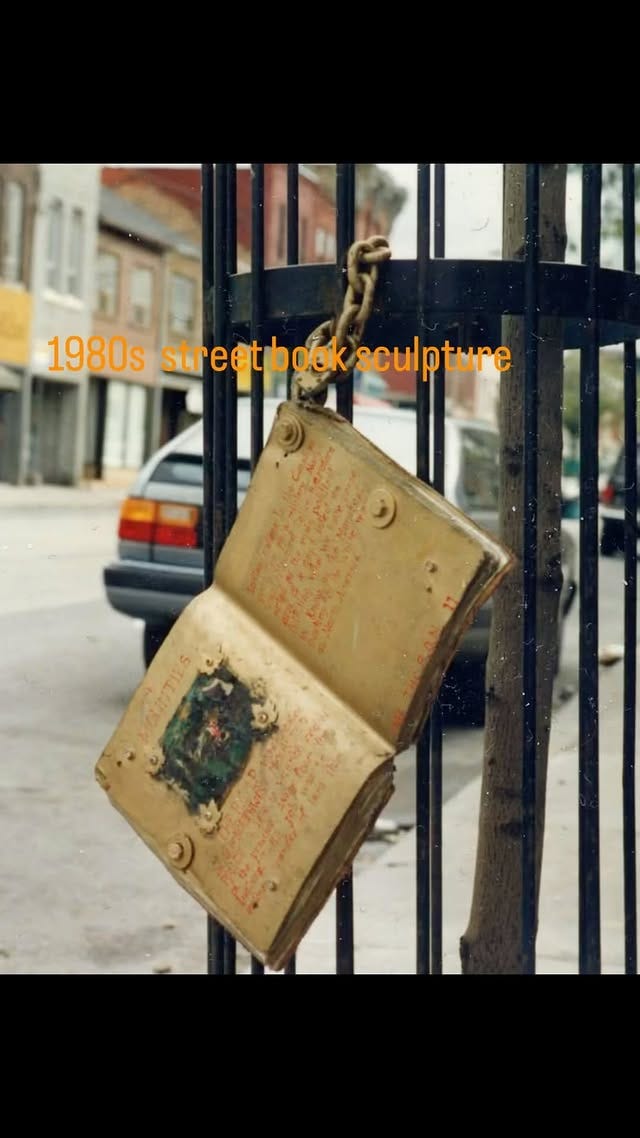

In all, the St. Stephen’s pole carries nearly a dozen pieces by the same artist, the oldest of which looks to have been there since 1985. I walked past it almost every day for more than a year before I was invited to take a closer look by jwcurry, an experimental poet and living library of eccentric Canadiana.1 “He likes this place,” curry said, eyeing the pole like a criminal profiler. “He always comes back here.” He told me a little that night about their maker, Rocky “Zenyk” Dobey, a street artist whose work curry’s described as being “obstinately about something in a sea of ‘I was here’s” (i.e. tags). He’d first attracted notice during the ‘80s and ‘90s, when painted books coated in metal or wax began to appear chained to posts at busy intersections,2 while area bridges sprouted coin-shaped concrete sculptures bearing Lenin’s profile. For decades, their source remained a mystery.

Since he began anonymously installing pieces in Toronto over 40 years ago, Dobey’s art has shown astonishing breadth: massive hand-painted satirical billboards; public memorials; intaglio-printed anarchist posters; and, most recently, large, intricately-detailed copper-plate etchings for gallery showings. Dobey himself has no idea how many pieces he’s put up over the years, but he guesses the number must be in the thousands.

These days information on the artist is fairly accessible. It came as a bit of a surprise after a few months of keeping an eye out for his work on the streets to find that he has a regularly-updated website and an Instagram account (@rockydobey). He even kindly consented to answer a few of my questions for this piece, sending pictures of his handwritten thoughts in response to my email. This kind of engagement with the public, prompted he says by his daughter, is still a bit novel to him.

“When I started I was just anonymous and didn’t think of [what I was doing] as art,” he says. “Nobody did. The term ‘street art’ didn’t exist. I just put stuff up because it felt good.” Dobey started installing pieces in the early ‘70s on Yonge St., where he worked as a shoeshine boy. From his very first efforts, he had both an off-kilter sort of playfulness and a strong anti-establishment bent. He recalls being obsessed with the photocopier at the old central library on College, using it to paper the neighbourhood with leaflets on how to get away with shoplifting at the Eaton Centre and strange invitations like, “DO YOU THINK YOU ARE TOUGH... WE MEET HERE SUNDAYS AT 1:00.” At Queen and Dufferin today, in fact, you can find a copper plate installed decades later bearing the same phrase. Like a lot of graf artists there’s something of the bored student in him, doodling variations of the same pictures (knives, towers, numbers, thrones) over and over in the margins of the world’s notebook. Far from being a flaw, however, this obsessive repetition is what gives the art its hypnotic allure.

A profile in (the long defunct) Poor But Sexy magazine quotes author Sheila Heti on Dobey’s work, which she calls an exemplar of “the best public art, which masquerades as the city, turning it into a place where expressions of gaiety and darkness manifest as authorless details.” I think there’s something powerful in Heti’s idea of art that mimics its surroundings, like a spider that evolves to blend in with orchids. Asking how art can “masquerade as the city” means asking what the city is, if it has some essential nature beyond being a hub of commerce. I spend an inordinate amount of time staring at rain-blackened bits of metal affixed to utility poles, trying to figure out whether I’m looking at a piece of municipal infrastructure or a worn Dobey original. When I do find some sign, even a battered remnant, it’s like touching the tip of a sprawling, submerged structure.

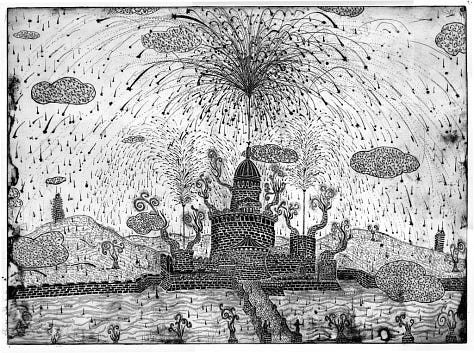

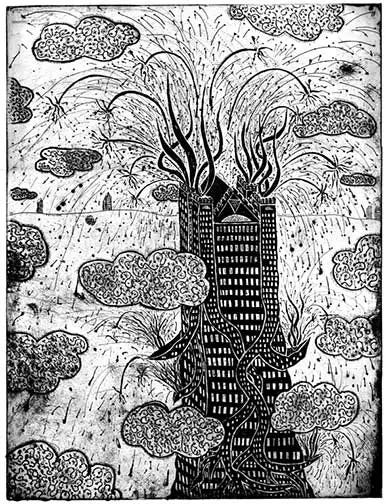

The installations are nodes to an alternative vision of Toronto, one which shadows the official history. In this version, those living in the streets are deemed more worthy of commemoration than the colonizers of the Old World. Opposite billboards boasting new condo and shopping developments, the buildings to come are depicted as baleful obelisks, their summits burning like the thrusters of rockets aimed at the Earth itself. Public monuments confer authority to the way those in power interpret the past. Because the city decides what can and cannot be built on public property, monuments conflate approval with objectivity. Dobey’s work by contrast makes seemingly random street corners crackle with significance: proof that someone felt something so strongly here that its impression has endured despite years of exposure. Though the pieces speak in a language of private symbols, they are also at the same time often poignant and direct.

Dobey’s not really given to reflecting on what he does. When I asked him if he thought about the memorials as a way of resisting time or loss, he replied that he’d always just done them. “My friend Ronnie Bouter died in [1977],” he wrote. “That really hurt me and I started to put up Ronnie memorials.” You don’t learn much about Ronnie from the pieces: he’s represented by a crude goalie mask, birth and death dates that tell you he died far too young, words like “I remember” or “I loved you.” But when any friend tells you about someone they knew who died, all you can really grasp, as they invite the ghost out from behind the red curtain to wave hello, is a sense of how that person once made them feel. Even the quarter-inch thick edges of these tributes are inscribed with text, as though to further delay the act of letting go.

For the bulk of Rocky’s career, once a piece left his Richmond Street studio, its fate was truly out of his hands. It seems likely he’d never have made art at all without this distance from his output. In a 2002 interview with Eye Weekly, he said his book installations “attracted the most attention but were the least successful artistically. That was one [project] where I was consciously trying to create art.”3 When I asked him whether he still felt suspicious of artistic pretentions now that he’s done a few gallery exhibitions, he told me he’d “had a really hard time accepting that [his work] was considered art. I guess I was just insecure.” This insecurity was intense: the Poor But Sexy profile recounts how he eventually became so spooked by the coverage the books were drawing that, in one frenzied night, he defaced hundreds of them with white paint. Things are changing on that front however. He now performs street installations much less frequently than he once did, focusing instead on gallery work and commissions. In a recent Instagram post he showed off a pile of dozens, if not hundreds, of unused plaques dating back to the ‘90s, complete with long mounting screws already attached. Strikingly colourful compared to the worn remnants I’ve seen, with painted highlights and the dazzling, golden-tongued lustre of freshly etched copper, it would be an incredible gift to wake up one day and see these “new” pieces on every corner. But, as he said in response to a commenter, “they don’t make sense to me to put up in 2018.” [2025 note: See epilogue for an update on this!]

Looking at the images from the ‘70s on Dobey’s website, I’m struck by how bare the city’s surfaces were then. His bold pieces must’ve stood out to even the most distracted passersby. Forty years on, what remains is being gradually swallowed up like jungle ruins. You almost have to know what you’re looking for to see them at all. Though Rocky says he can barely remember most of the things he installed, seeing them activates memories. “I find it comforting that I can walk around Toronto and see all the remnants of old pieces,” he says.

His more recent efforts find new ways to draw the eye. In 2013, Dobey was commissioned by the COUNTERfit harm reduction program at South Riverdale Community Health Centre to create a memorial for Toronto’s drug users. The result is an eight-foot copper statue in the shape of a curling flame, its surface covered with dozens of small etchings. Roaming around it, you can find many of Dobey’s trademarks, from a gilded throne to the number 13 ½, and even Ronnie B.’s goalie mask.4 But much of the space is also turned over to the people who use COUNTERfit’s needle exchange program. Scratching these simple tributes into the pliant copper publicly dramatizes the act of remembering, though the in-jokes and references are often only legible to an audience of one (plus one passed). The message of the piece is brought home by a mass of interlacing tendrils marked MOURN – REMEMBER – RESIST – HEAL. These tangled imperatives reveal no obvious source, and extend toward no clear end; for survivors, the process is continuous and undifferentiated. At the sculpture’s base, I found one small stone with only “forgive me” written on it in black marker.

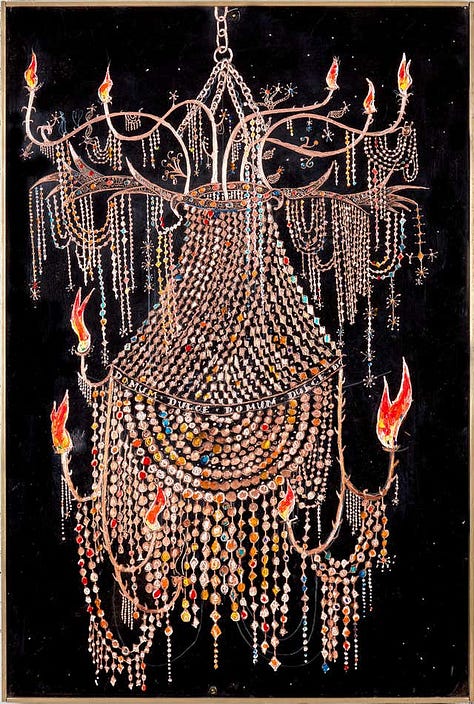

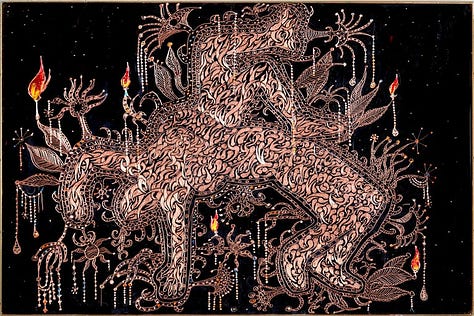

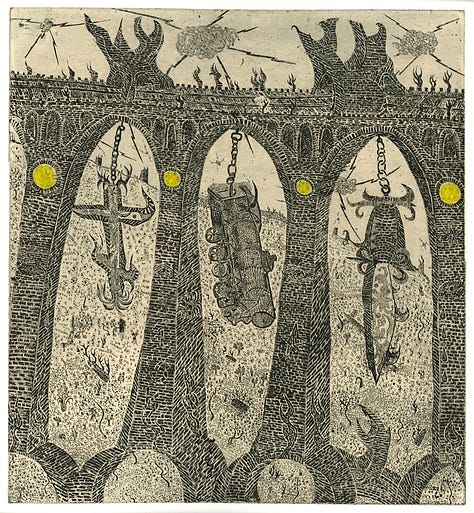

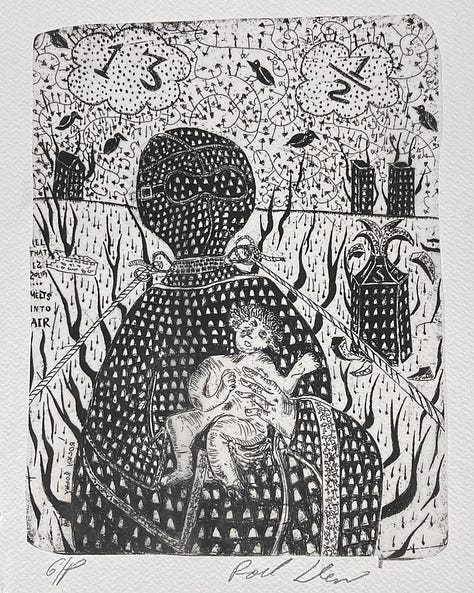

Ironically, by narrowing his canvas from the streets to images suitable for small gallery showings, Dobey’s art has become more epic in scale. His sprawling recent works look like compositions for an illuminated manuscript of the Book of Revelations, with Toronto’s architecture warped into magickal sigils, familiar Dobeyisms rendered as flaming prophecy. What his small street installations could only contain in part, these pieces seem to represent as a whole. But for Rocky, now retired from his job where as a welder he contributed to the city’s ever-looming skyline, his small studio has become as expansive as Toronto itself.

“I am loving sitting at my desk for hours at a time just lost in these intricate drawings,” he says. His work has made me feel the same way, lost somehow in the details of these familiar streets.

EPILOGUE

I left Toronto in late 2018, and would not get a chance to wander the city again till 2021. During the interlude, something wondrous happened: I shaved my head. Also, perhaps driven mad by COVID lockdowns, Rocky had gone on an installation spree to rival his ‘80s heyday. Kensington Market blossomed with dozens of new pieces, from bronze plaques on the poles to gold nuggets and bronze coins bolted to parking barriers and manhole covers. Even having seen how vivid Dobey’s original palette could be during my studio visit, it was still startling to see new pieces out in the world, like ancient Italian frescoes without the tasteful fade of centuries. It felt strange seeing the ruins returned to splendour, an old connection restored. As if to lay it on a little thick, a light blessing of rain began to fall. I only had a few hours in the city, and I was pulled along by my commitments past so many new treasures. I barely had time to rap each one with my knuckle in greeting, a habit I’d picked up during my old hunting days. But I felt no angst at missing out—I knew how long these marks can endure.

Rocky Dobey Addendum: A map of treasures

A guide to finding Rocky's work in the wild, plus the story of his "parasitic bench."

I wrote about curry and another of his Toronto street art interests, the once notorious p.cob_, in a previous zine called Nightshift #3, with Abigail Kashul. (Though the word “art” is probably an obscene stretch in cob_’s case.) It’s basically impossible to find except in a few random zine libraries, but I might re-post it here someday. curry is, in his own right, a delightfully perverse street artist, and a key figure in the history of Canadian experimental writing and publishing.

(The source of those rotating mounts I mentioned earlier.)

This one’s available as a .pdf on Rocky’s About page.

The significance of these icons seems to vary from piece to piece. The Illuminati-esque throne for example represents power, often societal; its backrest is often detailed with a globe or all-seeing eye, but it also has a transcendent quality when it’s undercut by the phrase “ALL THAT IS SOLID... MELTS INTO AIR.” The repetition of the number 13 1/2 originates from a prison saying (12 jurors + 1 judge = 1/2 a chance); it’s a reminder that the fix is in, and what freedom you do get in this life is largely down to luck.