The Vietnamese-Canadian writer whose family feasted while Vietnam starved

Kim Thúy is the scion of a colonial collaborator family and is an imperialist apologist

[This piece was originally written in 2024]

Kim Thúy, the Vietnamese-Canadian business lawyer cum autobiographical novelist, is back. There is Kim Thúy, on the cover of Elle Québec, dubbed an “eternal woman” (whatever that means) and talking up her Vivienne Westwood dress, which she claims cannot be “seen by your eyes” but only “felt with your heart.” There is Kim Thúy, making inscrutable claims in interviews that somehow Canada is “more communist” than Vietnam because Canada’s bankruptcy laws encourage entrepreneurship. There is Kim Thúy, praising Canadian freedom and claiming that her life in this country has been “a party” that never stops, a festive ball with constant horizons opening up in all directions. But why is Kim Thúy back? Well, isn’t it obvious? Her breakthrough first book, Ru, a slender little autobiographical novella adorned with fawning accolades, has finally gotten a film adaptation! This I discovered staring dumbfounded at that familiar morpheme in elegant serif letters, one above the other, on a wheat-pasted poster on the side of a condemned building, and I knew immediately that I’d find myself writing something about it, and that is because Kim Thúy’s Ru is one of the most vile and repugnant books by one of the most vile and repugnant people I have ever had the displeasure of reading.1

I’ve always been “perplexed” as to how a book like Ru won the Governor General’s Award. It simply could not be the writing, because Kim Thúy’s writing is absolutely atrocious. Take but one of many of Thúy’s comically-shallow metaphors, this one about brick walls the Communists built within the mansion she lived in as a child in order to subdivide it:

I went back to Vietnam to work with those who had caused the wall to be built, who’d imagined it as a tool to break hundreds of thousands of lives, perhaps even millions… I still don’t share the love for brick walls of the people around me. They claim that bricks make a room warm.

Only Thúy possesses the astute insight to subtly imply that “walls separate rooms from one another”—imagine my shock when I realized my apartment’s wall prevents my neighbour from walking into my bedroom—although she hasn’t yet made the leap to discovering that this function isn’t limited to red brick. Another material that one might use, for instance, is cement, a material Thúy’s family used to build the fortifications around her family home:

Our house was surrounded by cement walls two metres high with shards of broken glass embedded in them to discourage intruders. From where I stood, it was hard to say if the wall existed to protect us or to remove our access to life.

Did this cement “separate people”? No, of course not, it only separated Thúy from “authentic experience,” from her “access to life.” Not a thought is spared for those outside the wall and what the wall was meant to separate them from, and why they might be so desperate to “intrude” that the walls had to be topped with broken glass. While the corpses of maimed children lined ditches outside of My Lai, Thúy was being kept in the gilded prison of her own mansion, and somehow that is the experience we’re supposed to sympathize with.

Thúy’s “trauma” that her gratuitous mansion was subdivided, at first for the purpose of housing new governmental services (in this case firemen), and later so that several poor families could move in—ten families, in fact, the house was just that big—families who may have even lost their own homes to the South Vietnamese army and its American allies, is a display of such breathtaking and revolting narcissism as to suggest parody. Is Thúy having a laugh? Is the Governor General in on it?

But Thúy’s terrible writing does more than merely express hackneyed truisms about the functions of architecture. Sometimes it expresses disgustingly arrogant chauvinism too! Take this passage, where her father plays some communist soldiers Western classical music:

my father corrupted [the soldiers occupying our house] by having them listen to music on the sly. I sat underneath the piano, in the shadows, watching tears roll down their cheeks, where the horrors of History, without hesitation, had carved grooves. After that, we no longer knew if they were enemies or victims, if we loved or hated them, if we feared or pitied them. And they no longer knew if they had freed us from the Americans or, on the contrary, if we had freed them from the jungle of Vietnam.

These poors couldn't have possibly understood beauty, they couldn’t have possibly understood music. Forget that traditional Vietnamese music is just as rich and beautiful as anything composed by the masters of the Western musical canon and just as liable to make one cry. It’s just as likely that their tears were for what they had lost. Over a tenth of the population of Vietnam was dead. Generations were slaughtered. How many of Vietnam’s most talented musicians were now rotting corpses lying namelessly in fields across the country, victims of a war to uphold the Thúy family’s right to own a mansion and listen to classical music? But I can’t pretend to know why they cried, I’m never going to live in their heads and I can never ask them, and the fact that Thúy does pretend that she can do this exemplifies so much of her ridiculous narcissism. Forget trying to even figure out what it would mean to “free” these men from “the jungle,” which sounds like something you might hear coming out of the lips of the most unpleasant and on-the-nose Joseph Conrad character imaginable, demonstrating just how thoroughly Thúy identifies more with the culture of the colonizer than she does those of her own people, who are condemned to be lesser, ignorant, savage jungle people.

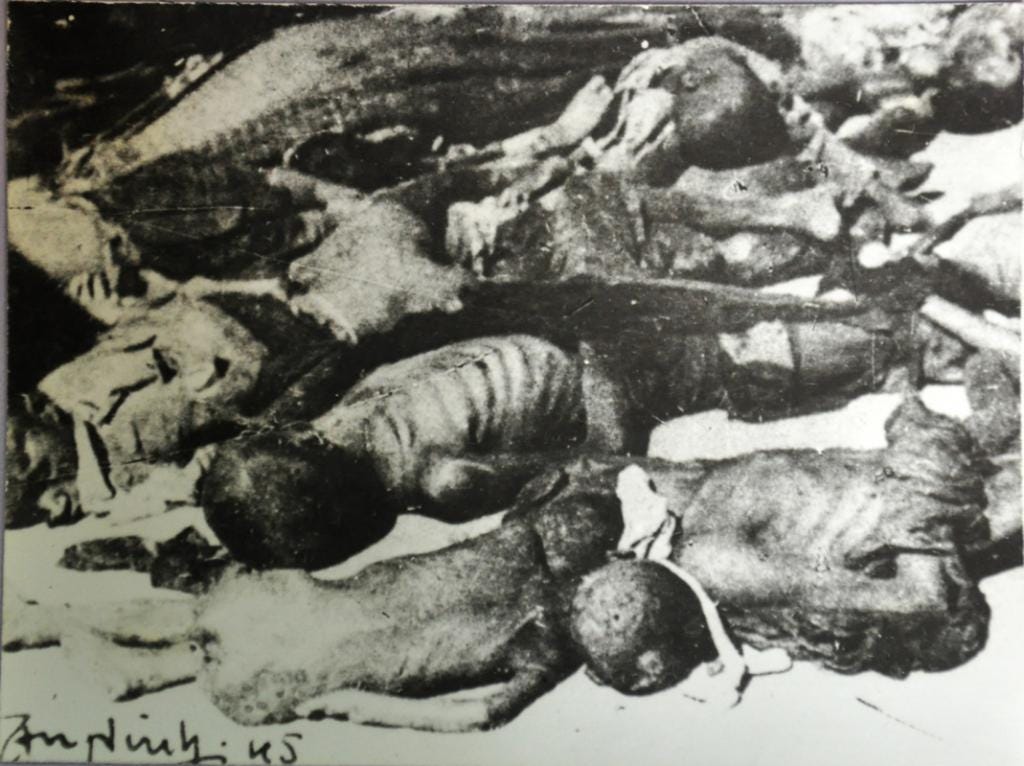

Thúy tells us several times that her grandfather was a colonial prefect, a collaborationist with the French colonial regime and, we might infer, its later Nazi-affiliated Vichy interpretation. Her father was educated in French literature at the Sorbonne. Her family had several maids and manservants, and at the very least two personal chefs. Her mother hadn’t worked a day in her life until she was thirty-four and spent most of her time “doing her hair, applying her makeup” and going to “social events.”2 When the French and Japanese colonizers her family collaborated with caused a famine in 1945 that killed as many as one to two million Vietnamese people, one can easily imagine Thúy, in all her dense Marie-Antoinette-esque “charm,” asking why it is they didn’t simply eat cake. How lavish were the dinners in the Thúy household as countless children’s emaciated bodies littered the streets so that the rice of Vietnam could be turned into fuel for the imperial war machine that fought to maintain their family’s privileges?

This was the price that the Vietnamese people paid for the Thúy family’s grotesque lifestyle.

Still, Thúy remains proud of these privileges, and can hardly hold back her contempt for the ungrateful serfs who took her place. They don’t deserve it enough because they’re ignorant of just how good it all is.

They say that ten families live there now... Do they know that they live in a building put up by a French engineer, a graduate of the prestigious National School of Bridges and Roads? Do they know that the house is a thank-you from my great-uncle to my grandfather, his older brother, who sent him to France for his education?

It is very possible that out of the ten families that now live there at least one person has looked into the history of their home out of curiosity? But even if they haven’t who fucking cares?! What is important is that they have a roof over their heads, not their appreciation for the tastes of the rich assholes who used to live there. But to Thúy, materialism and luxury is everything, one’s belongings are a mirror for the richness of not only themselves literally but of their interior life. When speaking of soldier-inspectors who came to her house, Thúy says: “an inventory of their belongings took three seconds, unlike ours, which lasted for a year.” Somehow, the crime is not in the Thúy family having so much and they having so little. The crime is that they didn’t get to keep it this way. But Thúy as a writer is so guileless, so narcissistic, so fundamentally stupid that she simply cannot help constantly telling on herself, because she lacks the shame or self-awareness to recognize what does or does not make her story sympathetic.

Stories like Thúy’s are laundered through the lens of “speaking her truth,” something deeply prized by western liberals even when it amounts to grievous lies by omission. The chemical weapons utilized in the protection of Thúy’s privileged lifestyle led to generations of Laotians to this day being born with horrible birth defects, but the fostering of historical, political, and geographic illiteracy condemns these statistics to the margins and “uplifts” the voices of the tyrants given access to the publishing industry without providing context to their subjective suffering, no mention of whether this suffering was in fact just desserts. It is the flattening trick pulled off by contemporary “identity politics” discourse—the “validity” of the oppressor is made equal to that of their oppressee on the basis of their shared skin colour—and it’s an invaluable tool in the arsenal of the imperialists.

The most recent season of Netflix’s Street Food takes place in the United States, often delving into that country’s immigrant populations’ peculiar derangements, such as Cuban-Americans in Miami who openly admit to the revolution having “taken everything” from them without hesitation, while letting the implications of a revolution against tyrannical serfdom “taking everything” from them speak for themselves. One of the most deranged narratives presented was that of Vietnamese-American restaurateur Thuy Phạm, who ends her episode by getting the South Vietnamese flag tattooed on her forearm. Phạm’s decision can be written off as simple naïvety since Phạm herself quite frankly comes off as being too personally vacuous to possibly understand what the connotations of that flag even are, but the scene’s uncritical inclusion in the episode as some sort of triumphant moment of cultural acknowledgement speaks of the continued rehabilitation of the supporters of tyrannical regimes as “speaking their truth” when they live abroad and happen to be “people of colour.”

When countless South Vietnamese flags predictably appeared at the right-wing January 6th protests next to Confederate naval jacks, “progressive” South Vietnamese revisionists were quick to snap to their defense. “The ideas of authoritarianism, of overturning the people’s will, are not the principles that this flag stands for,” declared the president of the Progressive Vietnamese American Organization, “it’s about us being free.” An odd statement considering the flag itself is derived from the flag of the French protectorate, its adaptation under quasi-Japanese rule, and the despotic American puppet regime that followed. One could ask Buddhists persecuted by the fraudulently-elected Diệm whether or not they felt “free,” including the protesters his regime met with chemical weapons to repress them. One could ask the families of the countless civilians who were detained by the South Vietnamese secret police without evidence; who were tortured, maimed, and killed without trial. One could ask the families of the innocent hostages whose heads were blown up with explosive charges in order to interrogate suspected Viet Cong members, or maybe even the families of those whose vital organs were fed to pardoned ex-convict South Vietnamese death squads to ensure their victims couldn’t go to heaven in accordance with certain Vietnamese traditions. By what stretch of imagination could South Vietnam have ever been considered “free”? Rather, it would seem that “authoritarianism” and “overturning the people’s will” are exactly the principles the South Vietnamese flag stands for, with “freedom” being entirely superfluous unless one counts the “freedom” to be a comprador. Even the Confederate States of America naval jack, the flag which appeared next to the South Vietnamese flag on January 6th, somehow has more positive and progressive connotations than those of the South Vietnamese flag when we consider at least the former’s (misguided) use by historical leftist anti-racist organization the Young Patriots, which is certainly saying something.

Ken Burns’ eponymous Vietnam War documentary in 2017 was an excruciating slog through a ton of piddling “both sides” nonsense (they get a Viet Minh vet to say “in war no one wins” on camera and he’s the first actual Vietnamese voice we hear), but it isn’t entirely without merit. For one thing, it does open with an incredible clip that no one seemed to question the wording of, wherein we are told “major support for The Vietnam War was provided by [list of rich bankers and the Ford Foundation].”

Hearing the phrase “major funding was also provided by David H. Koch” made me laugh so hard I nearly went to go meet him in Hell.3 But the series provides other benefits in addition to poorly-worded accidental confessions of the complicity of the American bourgeoisie in one of the most infamous years-long war crimes in human history—for all of its attempts to paint the war as being an ambiguous “both sides bad” conflict,4 it still winds up revealing enough to show how that narrative is absolutely bogus. A Vietnamese researcher for the RAND Corporation (and the daughter of a South Vietnamese official) talks about interviewing a captured Viet Cong fighter (she, like Thúy, is a chauvinist and admits that she assumed he’s be a “beast” and was surprised to discover he was just a man). She is shocked to learn that he is actually prepared to sacrifice his life for his cause, a concept she, the privileged daughter of colonial collaborator, seemingly could not comprehend. Here’s the clip so you can see for yourself: note her slight eye-roll when she describes his “just cause.”

The disconnect between the bourgeois South Vietnamese and their Viet-Cong-aligned countrymen is made even starker because the clip directly preceding that one is this:

Here, in sharp contrast to the bourgeois dipshit who simply cannot wrap her head around the notion of “sacrificing” for any cause, we hear the story of a mother who lost almost everyone in her family and living in constant grief nevertheless begging her remaining children to go fight. This is simply how tragically necessary the struggle was. The documentary obviously tries to frame this story as being a tragic tale of overly-enthusiastic engagement with the war-effort, whereas any reasonable viewer should come away understanding it to be a tear-jerking confession of desperation of the Vietnamese people to raise themselves up from under the boot heel of their oppressors, no matter what this Koch-funded slopumentary wants you to think. These are the people who gave it all to take people like Kim Thúy down.

When Thúy talks about the Vietnamese she uses “we” a lot, such as when she tells us that the Vietnamese have a “love/hate relationship” with their former French colonizers.5 Odd choice of words considering they employed her grandfather, and that the Thúy family got into Canada easily because their colonial educations meant they were fluent in French. Obviously this isn’t to say that there isn’t some degree of colonizer-identification in Vietnam that continues to this day as there is in any former colony—the Vietnamese religion of Caodaism, for instance, worships Victor Hugo—but the Thúy family’s relationship to that culture is a hell of a lot different than it is for common Vietnamese folk. Thúy has been back to Vietnam, for the record—as a corporate lawyer she worked to bring capitalist reforms to her home country, making her work not merely an ideological hammer for imperialism but a material one too.

I confess: I lied when I claimed to be perplexed as to how a book like Ru could be given the Governor General’s Award. In fact, I know precisely why it received the award, and I hope by this point I’ve demonstrated as such: Ru received the award transparently to elevate the imperial nostalgia of a vapid leech who misses her pampered days sucking the blood out of the Vietnamese people. It is apologia for the horrors inflicted by our allies abroad in an illegal war that killed millions and maimed countless more, a war we as Canadians are quick to distance ourselves from in spite of the material support our nation lent it. It is a book that is elevated in order to obscure the truth: that Kim Thúy’s family were the unambiguous bad guys—successive beneficiaries of French tyranny, Nazi tyranny, Japanese tyranny, American tyranny—and that the expropriation of their property was an ever-so-small victory for all of humanity, regardless of the trauma it inflicted on Kim regarding her aversion to “red brick.”

The true words I have for someone as vile and repugnant as Kim Thúy aren’t fit for print. I feel nothing for her family. What happened to them may only be described as “unjust” if one considers that what they actually deserved was probably a lot worse. A brief sojourn in a dirty refugee camp could have been a humbling reminder of the kinds of conditions families like Thúy’s kept their Vietnamese countrymen in for generations; instead, Thúy cannot comprehend the irony, she can only process the experience as a gross personal indignity. She is as dense and obstinate as a brick wall.

[If you enjoyed this piece, you may enjoy our piece on Roxane Gay’s ties to the exploitation of the Haitian people (which you can read here), or the stories of imperialist poets like Ilya Kaminsky and Dunya Mikhail who use their work to encourage the public to support hawking foreign policy (and you can read that one by clicking here)]

Before it is of course countered that Ru is a “novel” and not a “memoir,” I would like to point out that Thúy has several times stated plainly that the novel is more or less the story of her own life with some of the dates fudged. Even where certain details I take issue with are partially fictionalized, enough of it is nevertheless true so as to sustain my anger.

Read this excerpt and try not to fucking vomit in your mouth:

My mother waged her first battles later, without sorrow. She went to work for the first time at the age of thirty-four, first as a cleaning lady, then at jobs in plants, factories, restaurants. Before, in the life that she had lost, she was the eldest daughter of her prefect father. All she did was settle arguments between the French-food chef and the Vietnamese-food chef in the family courtyard. Or she assumed the role of judge in the secret love affairs between maids and menservants. Otherwise, she spent her afternoons doing her hair, applying her makeup, getting dressed to accompany my father to social events. Thanks to the extravagant life she lived, she could dream all the dreams she wanted, especially those she dreamed for us. She was preparing my brothers and me to become musicians, scientists, politicians, athletes, artists and polyglots, all at the same time.

It should be noted I suppose, in fairness, that David Koch did leave the John Birch Society specifically because of its support for the Vietnam War, which he saw as a pointless quagmire. But then again, I don’t really care to be fair to David Koch, because he was, among other things, in the John Birch Society.

I wrote an op-ed piece for Canadian Dimension last year where I have a section speaking at length about how the Viet Cong’s supposed “crimes” are not for us to condemn.

This interview also contains the incredible sentence “and now you know I’m just superficial!”