What do you get when you cross Jesus Christ with Charles Manson?

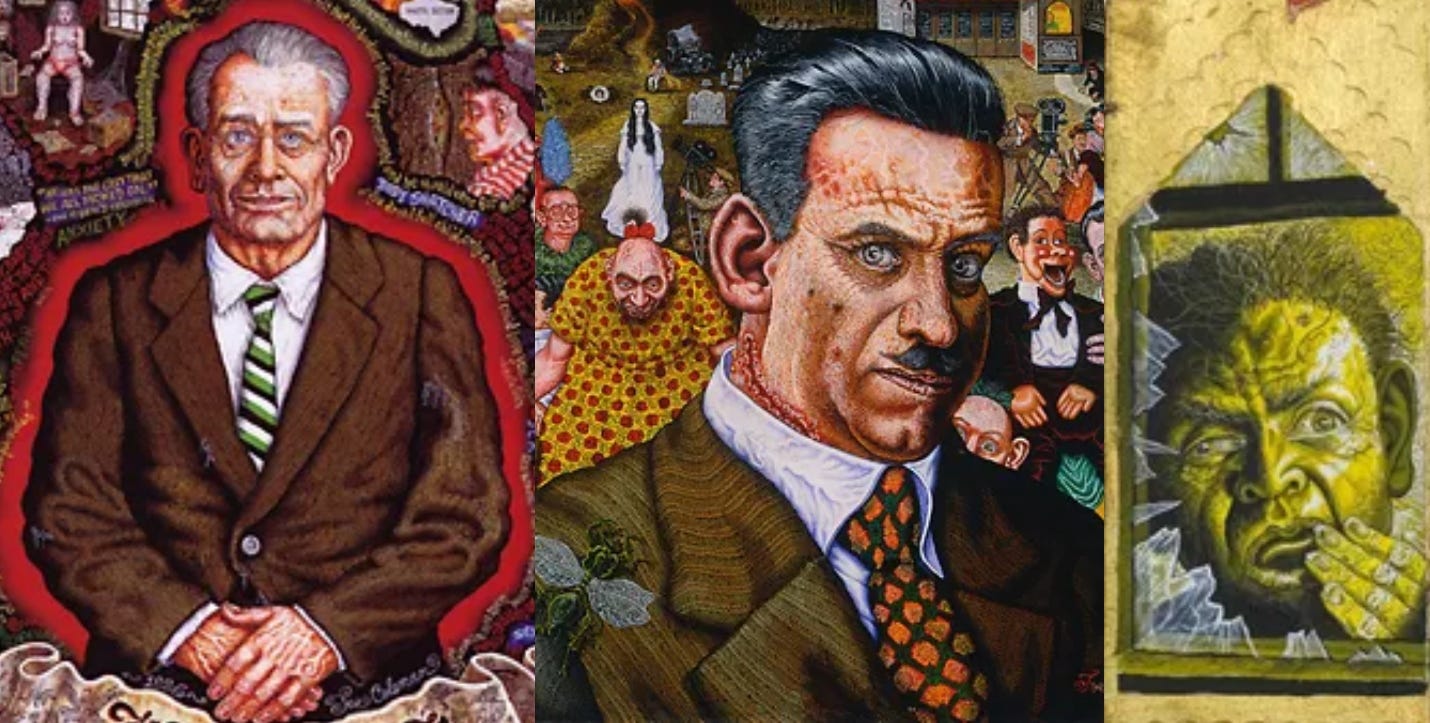

The infernal (and insipid) machines of Joe Coleman

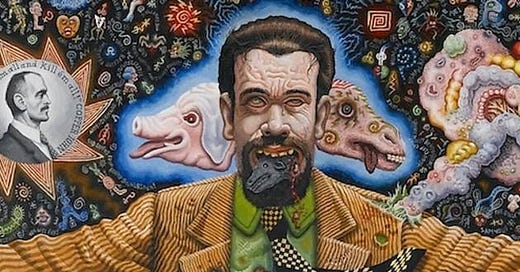

If you were to summarize the bug-eyed weirdness of the contemporary American psyche with one image, you could do worse than a close-up of United States Secretary of Health and Human Services Robert F. Kennedy, Jr.

Never mind that at this moment Kennedy is probably announcing his plan to combat the bubonic plague by force-feeding American schoolchildren live marmots. For the moment, just look at him.

He has risen! The fallen American God, returned as prophesied in a thousand tabloid-paper gospels—only the graveworms ate too much of his brain before Jesus got around to him and he’s all fucked up now, the familiar Kennedy features melted by one too many generations of Massachusetts Irishcest into a venous red mass that would cave like a rotted gourd if you gave it a light squeeze. (Also, he talks funny.) RFK Jr. is a literally cartoonish figure—more specifically, he’s a cartoon by Joe Coleman.

Although Coleman has not to my knowledge ever depicted a Kennedy, [Ed. note: He has! See footnote!]1 he’s spent most of the last half-century painting the rest of his personal canon of diseased American saints. Browsing through Coleman’s portraits of kitsch celebrities, carnival freaks, rapists, and wingnuts2 feels like a tour of American history as told by an immortal Phineas Gage. Like America herself, Coleman is an inexhaustible source of visionary inspiration and sheer brutish power, with the stunted, self-pitying soul of a boy who wets the bed and tortures squirrels. He is a great artist to the exact extent that America is a great country—and, as with any great artist, by considering his work you may unlock something crucial about his subject.

Joe Coleman emerged in the late 1970s from the alternative comix scene established by artists like Art Spiegelman (Maus), Kim Deitch (Waldo the Cat), and Bill Griffith (Zippy the Pinhead). He could’ve been among the best of them, but instead found his first notoriety as a shock artist. Here’s Spin’s Dean Kuipers on a performance (as his character “Professor Mombooze-o”) that resulted in one of Coleman’s numerous arrests:

“Boston, October 22, 1989. Reel after reel of ancient hardcore porno films flash onto a black screen onstage at BF/VF—the Boston Film/Video Foundation—grey and grainy, somebody else’s fucking and sucking memories of indeterminate age. After 20 minutes, the hundred people in the audience are quiet and disarmed. The lights come up.

Joe Coleman instantly comes whapping through the film screen from behind, hanging upside down from a climber’s harness attached to the ceiling, screaming and choking like a man condemned. This is the man everyone came to see. Green flames and acrid smoke belch from his chest as strapped-on explosives detonate under layers of shirt, ratty duck jacket and lab coat. Half a minute later, the booming and gnarling subside and Coleman’s wife, Nancy, leaps out and douses him with goats’ blood to put out the fires. She cuts him down and he tears away what’s left of the black screen to reveal a dead goat hanging upside down, twisting slowly. The goat is real. The odor of spattered blood and gunpowder seeps into the stunned crowd.

‘Here are Mommy and Daddy!’ cries Coleman, rushing to the front of the stage and pulling two live white mice from his pockets. He sits down on the edge of the stage and holds Mommy and Daddy up to his scorched beard and talks to them. Meanwhile, Nancy pulls out her Zippo and torches a cloth/plastic effigy of Coleman. The stage is consumed by fire as Joe screams at the squirming mice, 'I’ll eat the cancer out of you!’ and bites the head off Daddy, spewing it back into the audience. Then he snaps Mommy’s head: hers he swallows.

This is Joe Coleman’s stone ritualization of his mother’s death. Four days earlier, she had died of cancer.

The befuddled firemen who arrive minutes later are sure that this must be the meeting of a satanic cult. As police investigators pick through the chaos of greening humans, brown smoke and bloody carcasses, the owners of BF/VF finger Joe and Nancy, then fire manager Jeri Rossi. All three are arrested and Joe is charged with—among other things—an old Massachusetts blue law charge that hasn’t been used since the 1800s: Possession of an Infernal Machine.”

You can watch an excerpt of a similar performance in the 1988 pseudo-documentary Mondo New York, though I do not recommend doing so if you’re troubled by animal cruelty. As of press time, the full film is available here (Coleman appears at 8:16).

My first encounter with Coleman was picking up a copy of the Infernal Machine LP at a vintage shop here in Montreal. The record is a figurative soundtrack to the Mombooze-o character, which he retired following the Boston bloodbath. Side one (“Homage to Mass Murderers”) intersperses vintage country and blues murder ballads with exploitation film clips and interviews with murderers Ed Kemper and Charles Manson. Side two (“Infernal Machine”) is a collage of clips from TV shows and ‘40s films noir, audio from Coleman’s Mondo New York performance, and early live recordings by thuggish NYC noise punks Steel Tips.

The overall effect is eerie, and there are some powerful juxtapositions. The way a clip of Kemper’s tearful description of murdering his own mother segues into Eddie Noack’s 1968 recording of “Psycho” underscores the song’s unnerving potency; tucked between relatively jaunty tunes by Bessie Smith and Tex Ritter, a long excerpt of character actor Don Russell’s genuinely moving performance from 1963’s The Sadist (based on the Charles Starkweather murders) as a kidnapped schoolteacher begging for his life seems to represent man’s powerlessness in a capricious universe. Side two is bookended by excerpts from the 1947 film Nightmare Alley, in which a series of disasters reduce cocksure Stan Carlisle (played by Tyrone Power) from his position as a carnival barker to the role of a despised geek who earns a meagre living by biting the heads off chickens in front of jeering crowds. The implication is that, as Mombooze-o, Coleman himself has been similarly forced into the role of a freak by the diseased contemporary world.

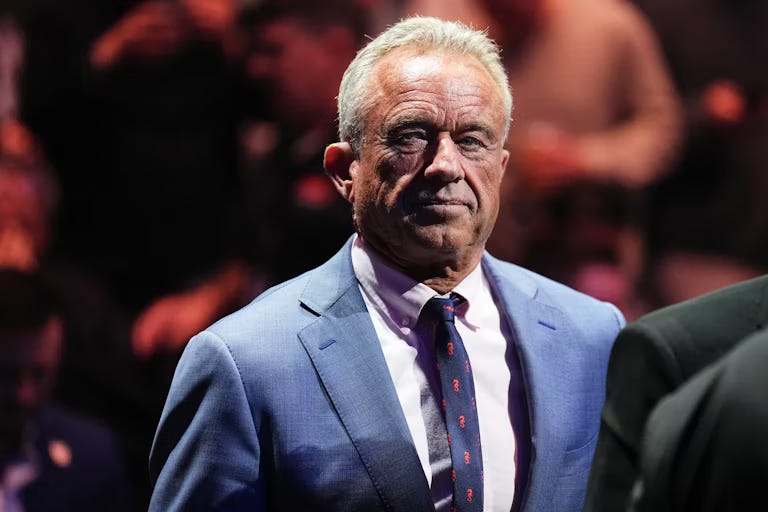

The LP includes a twelve-page booklet of Coleman’s paintings and, most interestingly, a picture-disc reproduction of details from its cover image, Portrait of Professor Mombooze-o. I’m not normally much interested in picture discs, but the sight of Coleman’s zombified head spinning on the table (and the dead fish bursting from his crotch on the flip) was like a carny hypnotist’s spiral wheel compelling me to enter a maze.

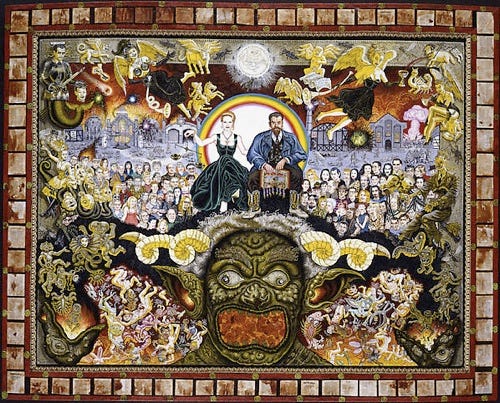

By the time Coleman decided he’d had enough of being worked over by the police department’s performance art criticism squad, he was already gaining greater renown as a painter anyway. His obsessively detailed paintings, worked out over months and sometimes years using a single horsehair brush, are the most successful transference of an alt. comix sensibility to the gallery I’ve come across. If the work in R. Crumb’s classic Weirdo anthologies could feel like a mutated, devolved descendent of the feverish iconography of sixteenth century religious art, Coleman’s paintings are that mutant culture’s return to high art. Early works like Baboon Heart Baby is Dead (1984) and The Nuclear Family (1984) feature relatively simple compositions, comix-y Lowbrow-adjacent takes on the sort of classical portraiture in which each object in the frame has some didactic significance. The figures are afflicted with boils and deformities and leaking wounds, the backgrounds so dense with obscene graffiti that the canvas seems to wriggle. As he entered the ‘90s, he became increasingly baroque (somewhere between Bosch and Howard Finster), creating dazzlingly intricate layouts in which a large central figure (often himself or one of his countercultural heroes) is surrounded by miniature panels depicting significant moments in their life. Many of his mature works are mounted on unusual objects, such as a shirt worn by an executed convict (1997’s A New York Pirate), and studded with found objects (like the medical paraphernalia on I Am Joe’s Fear of Disease from 2001).

His philosophy has changed little over the years, however. Coleman frequently conflates people like Charles Manson with Jesus Christ, saying in a ‘90s tour of his collection of oddities that he keeps a lock of Manson’s hair and a sample of Christ’s marrow displayed together. Falling back on the Blakean idea of a marriage of heaven and hell, he claims that if the pair’s DNA could be mixed in a clone it would create a perfect Messiah. However, the mingling of deviants and prophets in Coleman’s hagiographic art does not, as Coleman seems to mystically intend, elevate the former towards divinity so much as it pulls the latter earthward. Serial killers are, almost without exception, insipid creatures, powerless to explain their own behaviour with any real insight—as are for that matter, many holy men. Maniacs and religious figures are akin in the sense that each possesses intense evocative potential. A crazed killer’s actions, which seem both primal and alien, tear at the fabric of our notion of a shared reality. It is tempting to read their murders, being as superficially inexplicable as miraculous events, as though they are signs or portents, the killers themselves as visionaries. Put another way, both religious phenomena and psychopathic behaviour create a void of ostensible meaning that humans are agitated to fill. Meaning does not arise from their actions but is imputed to them by witnesses. In Coleman, these boring, broken men who kill find a witness capable of making them a genuinely mythic force.

In an interview with Richard Metzger on the BBC series Disinformation,3 Coleman says, contrasting himself with mass murderer Richard Speck, “I don’t want to kill anybody, but I want to express that pain. I want to express what he was trying to express. What if he didn’t have to do that? And maybe, just maybe, art is a thing where you can do that.” Ten years previously, Coleman told an anecdote in Mondo New York about covering himself in blood and harassing random women at New York bars; when their boyfriends would intervene, he’d light the fuse on the hidden explosives attached to his chest and then calmly walk out of the bar in the confusion, enjoying the screams and smoke. Whether he’s spinning a yarn or recounting something he actually did, it’s clear he gets the same petty thrill out of terrifying strangers as the sickos (both real and fictional) excerpted on the Infernal Machine LP do. This doesn’t make him a monster, but it does clarify that when he talks about “expressing” their pain he also wants his share of their freedom to do violence. Of all the reasons it’s good for Coleman that he ended up an artist instead of a cut-rate David Berkowitz, the most telling is this: if he had, what artist of his quality would’ve wanted to take him as their subject?

This is ultimately what pulls me back to thinking about the recent turn in US politics, the sense among the right’s perpetually aggrieved base that the low have finally been made high—when in fact they’ve merely been given license to indulge their depravities while the reek of their country’s gangrene rises like effluvia. Coleman’s too much of a genuine freak to become, say, the court artist of the MAGA Dynasty, but given that he basically has the political imagination of the Trashcan Man from The Stand, it would not shock me whatsoever if he ends up considering Trump (himself a symbolically evocative dullard) a messianic figure and producing some God-tier Ben Garrison work over the next decade. The former Mombooze-o always yearned to be the artist of the end times and, in a sense, he’ll probably get his wish.

Shortly after publication, intrepid reader

managed to dig up an illustration of Jack Ruby that Coleman did for Hustler in 1991, which includes his rendering of Kennedy’s partially a’sploded head. Click the link to check that out, and have a poke around at some most intriguing wares. Thanks DB!Original note: This despite JFK being shot on Coleman’s eighth birthday! My theory is that Coleman actually did paint RFK Jr., who then walked off the canvas and into our reality.

Plus a few celebrity buddies like Johnny Depp and Leonardo DiCaprio, whose patronage has made Coleman perhaps the richest outsider artist in the world.

The video includes an exegesis of Coleman’s 1999 painting The Book of Revelations, including an unremarked-upon close-up of what certainly seems to be Art Spiegelman roasting in hell as two demons go at his dick and balls with a crosscut saw.

He did a Jack Ruby illustration for Hustler 1991. If I remember correctly, Kennedy was innit.