Griffins Dropping "Canadian Poetry" Prize Worst Thing to Happen to Canadian Poets Since "Being Canadian Poets"

Dealing arms to fund arts, Margaret Atwood (again), and the War of 1812.

This is not “new” news: way back in 2022, the Griffin Poetry Prize announced that it was consolidating its two CAD $65,000 Canadian and international book prizes into a single $130,000 award which, despite being worth only USD $69,420 or so, made it the world’s richest single peppercorn for English poetry. Of course, this led to much choking on scones among the self-assessed middle- and upper-classes of Canadian poetry, who decried the move as an irreparable harm to the domestic verse industry—though not coincidentally many of these, like Steinbeck’s temporarily-embarrassed capitalists, also nursed the secret delusion that they were just one book away from winning the thing.

The change has not to my knowledge hamstrung Canadian poetry at large (yet!), but like clockwork the chorus resumes its complaints each year when the long and shortlists are announced. Thus far the prize committee has tactfully kept one toe in Canadian waters: 2023’s shortlist included veteran US-born Canadian poet Susan Musgrave, while in 2024 the Northern Ireland-born Canadian George McWhirter vanquished the likes of Fred Moten and Ben Lerner with his translation of Mexican Homero Aridjis’s Self-Portrait in the Zone of Silence.1 2025’s longlist similarly includes one Canadian, the Texas-born Dale Martin Smith, but given recent events this may not be enough to stop the grumblers from going full “third verse of ‘Not Like Us’” on Smith’s Canadian bona fides (and thereby those of the Griffins as a whole).2 Canadians have historically been eager to claim any notable figure with a tangential connection to the country as our own (The Rock’s dad was Nova Scotian!!), but this sudden interest in how Canadian someone like Smith really is uncomfortably mirrors America’s own resurgent nativism.

The poetry community’s Griffin angst predates the current stampede to rally round the beaver, but the latter trend is now fueling the former. The Venn diagram of 1) writers complaining about the prize and 2) writers who have recently posted a picture of the Burning of Washington (by the British) during the War of 1812 is basically a circle3—it seems perfectly Canadian that the locus of our myth of self-determination is an event undertaken by our colonial mama, while our conception of practical resistance is asking more loudly for money from one rich guy while we look out for maple leaf stickers at the supermarkets of another. The angst and the bluster are both symptoms of a deeper self-doubt: do we really have what it takes to defend the borders of our arts… or our nation?!

The gravy train and “The Shock Absorber”

Much has been made of the Griffin Trust’s great contributions to Canadian poetry. Besides its various prizes, the Trust throws an annual gala (sardonically/sincerely nicknamed the “Poetry Prom”); funds Poetry in Voice, a national poetry recitation competition for teens; donates books to libraries and prisons; and pays for poets to give talks at schools.4 The actual impacts of arts philanthropy are notoriously difficult to measure of course, but at a minimum we can say it has paid for a few field trips and put some money in the pockets of select poets. Perhaps some of those outreach programs have incrementally increased the audience for contemporary poetry, or put the right mentor in front of the right kid at the right time and seeded our next Anne Carson or something, who knows. If you choose to put more stock in these hypotheticals than I do, that’s your right!

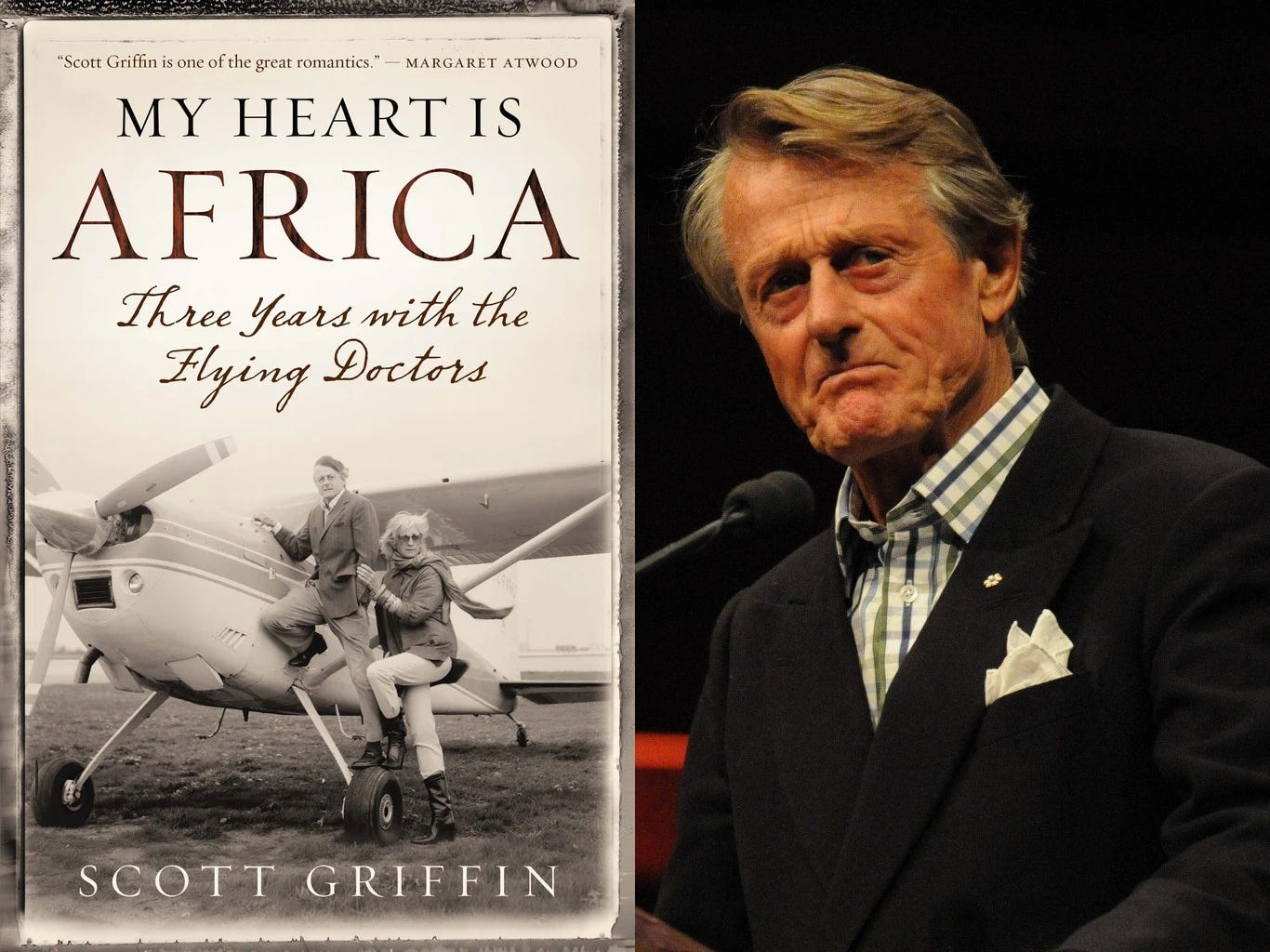

Less nubulous though is its impact on founder Scott Griffin, the poetry-loving multi-multi-millionaire and former industrialist-cum-publishing patron, whose yearly tax write-offs have greased his path to membership in the Order of Canada and purchased him Discordia favourite Margaret Atwood’s services as a press agent, among other baubles.

It has certainly purchased him an exception to the poetry community’s performative disdain for the ultrawealthy. Like George Soros or, I dunno, Tony Stark, he’s firmly seen as one of the “good ones.” In fact, in my experience the only thing that can stop a Canadian writer of a certain age in mid-rant about the oligarchy is to speak the words “Michael Lista,” which causes them to immediately make the sign of the evil eye and spit on the floor. Back in 2015, Lista, a cantankerous Toronto poet-critic, published “The Shock Absorber” with Canadaland, an exposé of Griffin’s profiteering (via his ownership of General Kinetics) from a $14 billion CAD arms deal between Saudi Arabia and the Canadian government. “The Shock Absorber” contrasts the plight of dissident Saudi writer Raif bin Muhammad Badawi, imprisoned and routinely publicly flogged at the time of the article’s writing, with Griffin’s privileged lifestyle. Between these two poles lie Canada’s poets, many of them struggling to pursue their dreams but nevertheless enjoying first-world freedoms. Just as the shock absorbers General Kinetics produces for Saudi Light Armoured Vehicles (LAVs) help to smooth the war machines’ progress as they grind protestors under their wheels, Lista asserts that the Trust’s fancy dress balls and promises of institutional approval have seduced the literati into performing the same service for Griffin’s public image.

I’ve already spoiled this part, but somehow the result of this was that in many quarters Lista was seen as the asshole rather than the guy running shotgun on the arms deal.5 Lista’s scabrous interview with James Lindsay of Open Book on the fallout from the exposé is worth reading in its entirety, but it starts with an unnamed former Griffin-winner’s declaration that he wished he could “‘throat punch’” Lista for writing the piece,6 and ends with Lista’s admission, “I’m more deflated than angry to be honest. Maybe a little grossed out by the ‘community,’ too. I was kind of hoping Canadian poets were going to be braver and better than they were.”

Well, thanks to Lista’s courage or tactlessness (depending on your position on the matter), by the end of the year Griffin had sold off his interest in General Kinetics. Future beneficiaries of the Trust’s largess could rest easy knowing that if they were accepting blood money, the blood was at least dry, and the wider community could continue glossing Griffin as a good guy for making the ethical choice to divest. (Raif Badawi, for his part, was jailed until 2022 and remains forbidden to leave Saudi Arabia.) While there certainly were other poets who called on Griffin to divest in the wake of “The Shock Absorber,” it’s telling that these days many are more upset by Griffin giving said blood money to foreigners than the fact that it is blood money.

Griffin’s Gulch

The community’s rationale as to why it’s okay to stooge for Griffin (and therefore that it is not unbecoming to whine about which passports prizewinners hold) seems to be that, while he is not a perfect patron of the arts, he’s pretty close, and we need those wealthy patrons or Canadian poetry will wither away. Given that this is a group of people who almost universally politically support some variety of welfare state model, if not outright socialism, the state must have really left poets in the lurch eh?

Well. As Amanda Perry notes in a (largely pro-Griffin) 2023 piece from The Walrus, “Per capita, American poets seem to have access to significantly less state support. Despite Canada’s much smaller population, the Canada Council budget for 2020–21, at $315 million, trails only slightly behind that of its American equivalent, the National Endowment for the Arts (324 million CAD). What Americans do have on their side is more Scott Griffins.”

Since Canada’s population is basically one-tenth of America’s, this suggests our poets are walking around with ten times the amount of public money per capita of our cousins to the south. Look, I would be very pleased if the Canada Council were even better funded than it is—I got a $4,500 arts grant many years ago for a project about gods fucking that I never even finished, which whipped ass—but, as with the US, the amount of money available to the state to support unreadable dreck about mythological genitalia is constricted by the existence of our own share of Scott Griffins, who squat over their undertaxed hoards of treasure. Kowtowing to this particular rich guy because he’s decided, over any number of objectively more pressing causes, to sprinkle some of that money on poets is pathetic. It’s like, if one of the guys holding a platinum-plated gun to my head decides to give me a handjob because he happens to be a handjob enthusiast, should I feel grateful? He didn’t do that shit for me!

The fact is, Scott Griffin set up his trust so that he could have his own name stuck to the covers of the “best” books of poetry of his time, despite having no known talent for verse—why else name the thing after himself? And further, if I were to guess why the Canadian and International prizes were combined, I’d put forth two suggestions: the first is that being able to say he gives out the single biggest poetry prize in the world makes his chest puff up. My second suspicion is that, as the prize committee has consciously started making an effort to recognize more demographically diverse artists over the past few years, Griffin has felt increasingly disconnected from the Canadian selections. He’s a Seamus Heaney and Dylan Thomas kind of guy. Can you imagine him making heads or tails of Jordan Abel’s Injun or Canisia Lubrin’s The Dyzgraphxst? It’s less fun watching someone hand your money over to books you don’t get, as opposed to the more traditionally lyric poets like Don McKay and Margaret Avison who dominated the first decade of the Canadian category. A measure of fickleness and boorishness is nearly always the price of hitching your wagon to an oligarch.

I’ll shoot myself if no one asks me to Poetry Prom

Ultimately, the most intoxicating thing Griffin provides the Cinderellas of CanLit is a few nights respite from feeling like unwanted dorks, a frisson of the luxury that on some level a lot of artists like to think they deserve. Billy-Ray Belcourt cried onstage when he won the Griffin, and you would’ve too if you were 23 years old and someone said you were the best at poetry and they were giving you $65,000 (CAD) for it. At his age, I nearly cried when I got a pass to a week-long festival’s VIP lounge so I could drink wine and fill my backpack with sandwiches every night. If some rich guy’s fool enough to leave his money out, I will always inveigh you to grab all you can. But I can’t help but think back on an interview Ken Babstock did with CV2 magazine not long after his own 2012 win. When they asked him how it felt, the gist of his answer was, “The money’s nice, and I felt really great for a month, and then I woke up one day and felt like shit again and that’s about it.”

Babstock is not a wealthy man, so if that’s all that that amount of money and a shiny award brought him, that suggests to me that any fancy carriage provided by the Griffin Trust turns back into a pumpkin (or an LAV) pretty quick. Frankly, we’ll all be fine without it.

With that said though, if all this really is more about recognizing the best in Canadian poetry than it is the allotment of a rather gauche wad of cash, I have a solution. I’m pleased to announce that Discordia Review will be handing out the 2025 Peter Griffin Prize for Canadian Poetry. While our endowment is considerably more modest than that of the Griffin Trust, we will be offering the deserving winner a total of $6.50 (CAD, of course) and each of the shortlisted readers will be granted a generous $1.00 honorarium for reading at our gala. We’ll even make stickers the publishers can put on their book covers, just like the other guys. Stay tuned! (And Peggy, if you’re reading this, call me?)

Unlike most prizes, the Griffins consider translators as the “author” when recognizing books which were originally published in another language. It’s a bolder position on the question of authorship in translation than most comparable institutions take. Per the Trust’s website, the “international prize of C$130,000 is shared 60% to the translator, 40% to the original author.”

Let’s be clear: few of the people grumbling about this on Facebook could mobilize to reinstate a lapsed membership in the PC Optimum program let alone the Canadian category at the Griffins, but eh, I needed something to write about today so go with it.

I’m going to let Comrade Eris field this one: “If I see one more fucking dullard say some shit about how ‘wE bEaT dEm iN Da WaR oF 18!2!!!’ I’m liable to pop my own brain like a fucking pimple. Listen, you fucking troglodytes: Canada didn’t win shit. Somehow, while you were imbibing that state propaganda they fed us in grade school, you failed to perform the simple act of counting that would lead you to realize that ‘1812’ comes before ‘1867,’ which was the year of Canadian Confederation. The independent state of ‘Canada’ did not fucking exist in 1812. The war itself was not even fought by people from Canada. Outside of the York Volunteers, the vast majority of the fighting forces were either British regulars imported from Britain or else Indigenous warriors. (Ironically, actual settler residents of Canada a few decades later would sign the Montreal Annexation Manifesto and demand to be annexed by the United States.) The War of 1812 was not between a powerful America and a scrappy Canada, it was a war between the upstart fledgling nation of the United States and the British Empire, AKA the world’s greatest military power. The Americans, who were the underdogs in that fight, were betting that British engagement in the Napoleonic Wars would make them too distracted to defend Canada. They were wrong. They lost. If this war were to happen again today, it would be America, now the greatest military superpower on earth, vs. Canada, its pathetic neutered vassal. There would be no ‘burning of the White House.’ The most we would be able to hope for is years of protracted guerrilla fighting within Canada, with extremely high Canadian losses, until maybe we—’ [Eris was dragged away from the keyboard and brought somewhere calm and safe—Ed.]

The latter idea conjures some incredible scenarios. School administrators: You too could have your students terrorized by Christian Bök! Invite Robin Richardson to wellness-grift their lunch money!

It must be noted that Lista may well be an asshole, I don’t know. Before “The Shock Absorber” he had already earned the ire of many in the scene for [summary of antiquated bickering no one gives a shit about anymore], and clearly enjoyed cultivating the role of “brash truthteller” in interviews. Which is fine, it just didn’t help his case.

Smart money’s on John Ashbery.

That was fun—Merci Sire. For the phlegm I’ve occasioned to be produced from the mouths of Canadian poets, all I can say is: I hope there’s a grant for them for that. The money line is off on JA being behind the throat punch threat though. That came from someone a lot closer to home, if you know what I Mean.

I know it’s fun and easy to look at something on the surface and make assumptions.

But if you knew the whole story, the spiritual psychosis, the full-on collapse, the part where I ended up unhoused and talking to myself on the streets at 85 pounds, you’d understand it didn’t start because I thought spirituality would be a good business idea.

At the time, I was running Citadel, my writing mentorship business, and making the best money of my life. I’m not ashamed of that. I like paying my bills. The “pivot” to spiritual content wasn’t a business move. It made me nothing, aside from a sliding scale free I charged for rare one-on-ones. I was someone who believed she had found something profound and wanted to share it.

I still believe that.

I know from the messages I received that thousands found comfort and clarity through what I shared freely, through a podcast I made no income from. I think over the course of 3 years I make 17 cents on TikTok and all in about 900 on 1-1- sessions - most of which I offered for free to people who could not afford to pay. Not that it would be terrible if I did make money off of sharing my experience. Do you make money?

I was destroyed by CanLit long before this, always through a knee-jerk reaction, a shallow read, a rush to diminish and twice now involving lies told by Jake Byron - whom I have never actually met but who sure seems to have it out for me (his attack of my podcast came days after I deleted twitter and weeks after I blew my life savings on a house) He obliterated me and no one thought to fact check.

I remember tearing down my lucrative business because I didn't want to help people write their books- that felt wrong to me - I wanted to help people "awaken". Is that insane given I just started waking up myself? Yes. Is it evil and money-motivated? I can tell you from the truth of being the only person with actual access to my intentions: No.

I get that you guys are materialists and think that this stuff can only be made up and therefor I must have made it up, but I assure you I lived it, brutally. I still am living it - like the mushroom trip that never ends. I didn't do it on purpose. The lockdown snapped me and there I was, no mentor to ground me, just wide-eyed and talking to angels in my bathroom while hiphop lyrics tried to seduce me into a motel in Niagara Falls (long story) which you'd know if you actually listened to my content.

So I’ll say one “woo” thing (if you're still listening)

During that time, I had a near-death experience. It was exactly like people describe, your life flashes before you. But it’s more than memory. It’s an inventory. You see the harm you caused. The things you missed. The effect of your words, even the casual ones. You learn. And it changed me. Maybe you’re not in a place to self-reflect. Maybe you don’t believe in any of this. That’s fine.

But I’ll leave you with this: I’m Robin Richardson. I was dragged through hell by a spiritual awakening I didn’t ask for. And no I don’t regret trying to share it.

I would love to actually engage in a discussion with one of you, face to face about all of this. Until you experience it yourself it's impossible to really know what it's like to have an entire community "know" you and "know" you need to be destroyed without ever actually meeting you, talking to you, or even deeply listening to your content.

I lost everything.

But I helped people.

And I would do it again.