About this whole 'Neo-Romantic' thing

Gioia, Gasda, Goethe, and the galvanizing gospel of a return to gothic grandeur

Who are these “Neo-Romantics”?

We need to stop coining the term “Neo-Romanticism.” It feels like every ten fucking years we have to re-litigate whatever the fuck “Neo-Romanticism” is: there were plenty of late 19th-century poets like Rilke and Yeats who often get dubbed “Neo-Romantics,” there was the French painting movement dubbed “Neo-Romanticism” (sort of a proto-Stuckist movement) which is not to be confused with the similarly dubbed “Neo-Romantic” landscape painting movement in the UK which existed contemporaneously, and I’ve seen the Decadents and their multitude of contemporary variations get called ostensibly “Neo-Romantic” and I’ve seen Tennessee Williams get called a “Neo-Romantic” and Terence Malick get called a “Neo-Romantic” and the whole David Foster Wallace et al. “metamodernism” thing get called “Neo-Romantic” and I read a Pitchfork article a while ago that saw the music of Harold Budd get called “Neo-Romantic” and I’m sure they’ve called plenty of other shit “Neo-Romantic” before and since and of course there’s the fucking post-glam New Romantic subculture and music scene in the 70s and 80s and there have been calls for a “Neo-Romanticism” ranging from Nietzsche’s contemporaries who railed against Naturalism to Richard Rorty’s claims that a return to Romanticism was needed to overcome the ironism of postmodernism… guys. Enough.

wrote a widely-shared (and worth reading) article about how we’re entering “Neo-Romanticism,” which he claims he predicted a couple of years ago in a different article, which itself claims was an outgrowth of a shitpost he made several months before that and… hang on, I distinctly remember Gioia making claims more or less to this effect in the final chapter of his book The Birth (and Death) of the Cool more than fifteen years ago where he likewise predicted some mass counter-cultural reaction in the same style against more-or-less the same things and it didn’t happen then, in fact his claims in that book that we were seeing the “abandonment” of irony in 2009 were about as off the mark as you could possibly get. Gioia points to quite a few articles that claim to assess the rise of a new “Romanticism” but, having read that Ross Barkan article and the others he links to, I’ll point out that though these pieces says much about Byron and Blake and whoever they fail to establish just who the analogous “guys” are of this supposed revival. Who are we pointing to? Who are the “Neo-Romantics”?It’s not like I’m necessarily against the idea. Our own collective’s Poetry Heel wrote a screed that in effect advocated for a return to a position that very much sounds like a kind of “Neo-Romanticism” in effect (though I’ll be damned if I’m going to perpetuate the continued abuse of that phrase by labelling it as such). But without specific cultural figures to point to who are leading the charge, all I see are commentators standing at the sidelines waiting to describe it. If there’s anything there there then it’s a ship without a captain. I don’t even know if it has a crew. Is there even a ship at all, or are we all just drowning in the sea? As Andrew Pfannkuche of Socialist Realism points out, we are in a culture lacking a political imagination to realistically escape the dominance of the technocratic and algorithmized nature of its present circumstance. I believe that Gioia is right about the need for something imbued with the vitality and enthusiasm of Romanticism, but whether such a thing truly manifests remains to be seen.

Matthew Gasda can’t tell what a “Romantic” is in the first place

I was surprisingly seeing eye-to-eye with the opening remarks of a piece by

(of all people) where he begins by expressing what I think to be a central and important question that the aforementioned Socialist Realism piece seemed to be grasping at as well: can those living today really ever access the radical freedom the Romantics pursued? Still, Gasda cannot help but show his soft conservative underbelly when he says that the killing of Brian Thompson was little more than “bathos or Promethean performance art”—I don’t personally see how Mangione’s act could be said to be any more or less bathetic than Byron’s own dying among the Greeks—a claim probably borne out of the fact that (so sayeth my Rumour Mill) Gasda is apparently taking handouts from Peter Thiel, and I don’t think it’d endear him to the billionaire class to be celebrating their assassinations.If we’re going to talk about Neo-Romanticism we should probably understand what Romanticism really was, and Gasda’s piece is a good place to build from because it gets so many things about the movement wrong that need to be corrected. Gasda does much to depoliticize the Romantics, but the fact is that the Romantics were in fact a very political movement, flawed though those politics may have been. The Romantics were explicitly pushing up against what they saw as the dehumanizing post-Enlightenment industrial world, and the ethos of this rebellion was not just aesthetic but in fact deeply economic and political. Shelley himself once said that he considered poetry and arts to be subordinate to political science, and even married the daughter of two of the most prominent political thinkers of his age. In their youth and at the height of their poetic accomplishments, Wordsworth and his friends were great extollers of the virtues of the French Revolution. Where exactly would Jean-Paul Marat fit into Matthew Gasda’s bathetic hierarchy?

Gasda mostly winds up talking himself in circles while making drastic over-simplifications. Case in point:

A new age of Romanticism would not take much interest in Substacks about Romanticism or take part panels about AI; it would be off in the woods, or on the highway, on a motorcycle on the run; it would be reading by the fire, taking marginal notes; Romanticism would be having more sex, too.

Well, I can opine on this as an outside party to all that, because it’s not that I’m not having sex because of the conditions of modern life, I’m not having sex because I’m married HEYYYYYYYY i get no respect i get no respect im tellin ya

(Ed. note: My spouse would like to inform you all that we have a normal and healthy sexual relationship.)

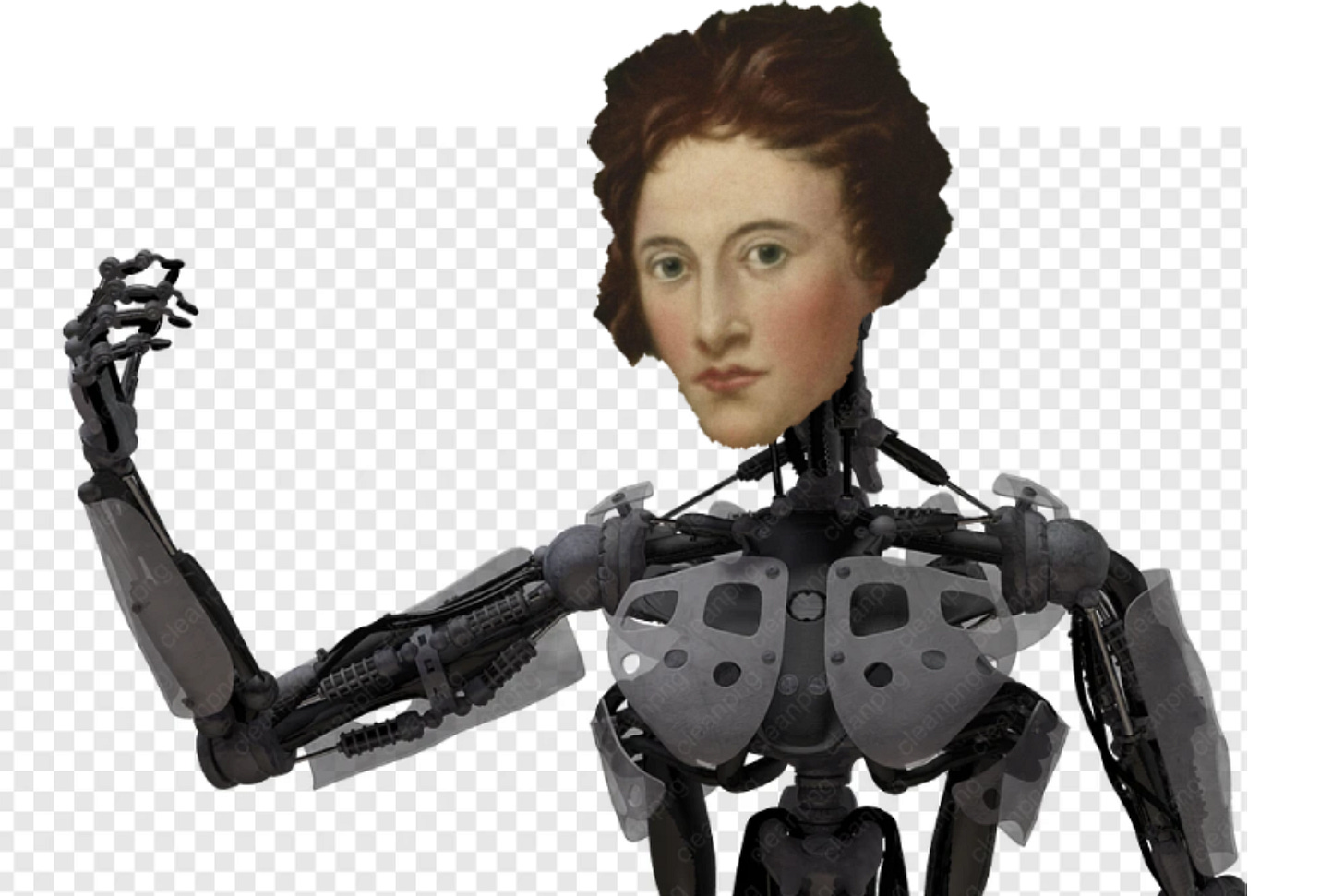

But anyways, Gasda’s idea of Romanticism, his claim that Romanticism would be less interested in Substack posts of manifestos and more interested in being on the road, in the woods, reading by the fire, etc., is ironically a very pop-cultured idea of what the Romantics actually were, more in line with what Taylor Swift seems to think they were than their reality. In response to Gasda’s further claims, that the Romantics were “not cultural commentators,” I implore him to scroll beyond the first paragraph of their Wikipedia pages, because they very much were. They commented extensively on culture and wrote plenty of essays about it (Shelley’s “A Defense of Poetry,” Blake’s scathing annotations on Reynolds, basically Hazlitt’s entire body of work), they even wrote critical comments about one another (Coleridge’s attacks on Wordsworth in Biographia Literaria, Byron’s satire of Southey in The Vision of Judgment). The only reason they weren’t doing this “on their laptops,” as Gasda puts, is obviously due to the fact that they had no fucking laptops (although Lord Byron’s daughter would coincidentally wind up being the godmother of the modern computer).1

The thing about “Neo-Romantics,” whatever we want to say about them, is that they would be, as the name implies, Neo-Romantics. If such a thing is to come into existence it will be by its very nature something unique, it will be quite different—you cannot simply transpose the Romantics to today, because they are an expression of a certain form of material conditions that are no longer the case. It would be extremely silly to chastise the Renaissance on the basis that it somehow was not exactly in line with the Classicism that it was being inspired by. The Renaissance was a reaction to the conditions of its own time, not the conditions of Ancient Greece, because that’s not where or when they were living. To do the former would be bland pastiche.

So what? What are we supposed to make of all this?

Going back to Rodney Dangerfield of all people, he once said: “At twenty a man is full of fight and hope. He wants to reform the world. When he is seventy he still wants to reform the world, but he knows he can't.” That cap is going down all the time. Now for a man of twenty—hell, even a boy at fifteen—this is reduced to a struggle for hope, a desire for hope—more than anything, a reflexive second-order hope, a hope for hope itself. An adaption of a Romantic ethos would not be as prescriptive as someone like Gasda might say and it could take many forms, but could it truly be said to be what it is without at the very least an authentic sense of hope?

The original Romantics faced existential questions regarding the vitality of life and nature faced with the incursion of the factory. While there was often a defeatist attitude included in their work—a sense that what they railed would inevitably be “victorious”—it was nevertheless contrasted with a simultaneous vibrant will and belief in ultimate ascendant virtues. The realities of industrialism killed the first Romanticism. Realism and Naturalism traded Romantic fairy tales for engagements with the bleak realities of this new world, out of the thinking that through frankness rather than idealism the world might actually be changed. Caspar David Friedrich’s wanderer there above that sea of fog became the cavernous mines of Zola’s Germinal, wherein mankind’s mechanical fist reached down into the pits of Hell so as to strangle the devil himself and usurp him. To accept the realities of the sublimity of mankind’s own wrought horrors was hoped by the practitioners of these styles to be enough to muster change as well—they failed too.

We are building ourselves up on the shattered remnants of layers and layers of the revolutionary failures of compromised, co-opted, or crushed ideological tendencies, a Hegelian chronostratigraphy of the human race, as we stare down rapidly approaching existential threats we seem to have no ability to stop. Can real hope exist in this environment outside of dangerous delusion? Can this central Romantic conceit of hope and wonder authentically thrive in our times? It remains to be seen.

Let me make one thing clear, however, lest I fall into a common trap of misrepresenting the Romantics myself: the Romantics were a very pluralistic movement. The English Romantics’ Lake Poets were never really in line with Blake who was very much a sui generis figure, to say nothing about the conflicts between the English Romantics’ first generation and its second, or that second generation’s own condescension toward Keats. Differing historical circumstances in different countries likewise led to very different Romanticisms—whereas England was rather “stable” at the time, French Romanticism was emerging out of a series of successive political crises and therefore its tone was often more obviously social and political, while German Romanticism was very much concerned with the nationalist preoccupations of its era and more invested in interrogating the national spirit (the Volksgeist) than the universal natural one. To say that the Romantics were one thing and one thing only is a flattening of literary history. They were extremely dynamic.

the peter thiel thing is absolute garbage --take it out--my plays are funded by kickstarters--all of which you can look up; we have a tiny budget, self evident to anyone who knows me or my work; do a minimal amount of homework, don't cite "the Rumor Mill"