Six undiscovered private press folkies you've got to hear

Featuring Tarp Clancy, Liesl Eddy, and the "Mad Crawdad."

As the vinyl revival lurches into its twentieth year or so, it sometimes seems like we must surely have found all of the undersung folk artists worth unearthing by now. How many more Connie Converses can there be out there, how many Jim Sullivans or Elyse Weinbergs? Still, the allure of history’s unswept corners corners remains, and every year the canon of beautiful also-rans expands.

Discordia Review reached out to ethnomusicologists J. Mattingly Furstenau of the Tangier Folk Music Insitute, and D. John Chrystler, Osgoode Hall Law Special Collections, to learn about some of the even-lesser-known artists still waiting on their flowers.

Tarp Clancy

The reclusive Clancy recorded a series of 10” EPs in the early 1960s at his rudimentary cabin studio in Muhlenberg County, the heart of Kentucky coal country. An elderly former miner who had lost most of his picking hand when a vial of nitroglycerine he was transporting ignited in his glove, Clancy homebrewed a mechanical strumming prosthesis. He would loop a cord around his neck that allowed him to cleverly control the tempo of his metal claw by moving his head and shoulder, though over time he began to suffer from nerve damage and light-headedness from the way it constricted blood flow to his brain. The EPs, recorded solo on acoustic guitar and dulcimer, have a poignant jerkiness to them that matches his lyrical obsessions with isolation, tribulation, and grisly industrial accidents. They were distributed in extremely limited quantities through ads in the local Baptist church’s circular and were forgotten until one of the discs was discovered by Brooklyn DJ Anathius Taylor at a goodwill while visiting his family home (Beechland Plantation). Clancy himself disappeared (nearly) without a trace sometime around 1970, though in 1985 a claw of his design was discovered buried under the Jefferson Davis memorial in Fairview, Kentucky during routine maintenance on the obelisk. — J.M.F.

Key song: “Cold Fingers”

Remy “Mad Crawdad” Beauregard

Beauregard grew up in a vibrant 1920s Louisiana Cajun community and learned to play guitar from his father. His parents raised him to venerate Governor (and later Senator) Huey Long, and the day Long was assassinated was the day Remy Beauregard would say he lost his innocence. “It was like being told they killed Santa Claus,” he later wrote in his journals, “I felt all the magic and hope in the world drain from me in a matter of seconds.” Despair drove the young man to street crime, joining the infamous Les Gamins gang, and he soon ran afoul of the law. A boy called Remy Beauregard went into juvie, and a violent criminal called “The Mad Crawdad” came out, albeit one with a remarkable gift for the accordion.

Remy had a few close calls with greatness: after visiting 439 Baronne a few times, and even getting to jam with the legendary George Girard, Orin Blackstone made moves to begin recording the young man. Only two recordings survive, “Where, Mother?”/ “Dandelions” and “I’ve Got Nine” / “Life Will Screw You,” the latter an extremely rare shellac 10" thought lost for decades. Unfortunately, another run-in with the law hampered his burgeoning musical career, as Remy bludgeoned a man to death in a drunken bar fight, spending the next six weeks in prison. While in the slammer, Remy found Jesus, and upon his release the newly sober musician recorded the Forgiveness LP. It is a desperate and cynical record, the product of a self-loathing man seeking a salvation he knows he will never achieve. His sobriety would be short-lived, and he drank himself to death in 1957 having lived a life in near-complete obscurity. His final single, released posthumously, was titled “Why Did You Leave Us, Mr. Long?”

A career-spanning compilation is set to be released by Light in the Attic records in late 2026, titled Crawdad Sings! with liner notes by Dan Auerbach of The Black Keys. — D.J.C.

Key Song: “Life Will Screw You”

Jeramie Laramy

The Vietnam War inspired some of the most powerful protest songs of the 20th century, from “Eve of Destruction” to “Napalm Sticks to Kids.” But Jeramie Laramy stood virtually alone in 1975 when he sang the words “first my mother left me / with a man called Dan / then my country abandoned the brave people / of South Vietnam.” Laramy was a Canadian who renounced his citizenship and moved to San Francisco, California in 1967 in hopes of being drafted, but due to his complicated residency situation he was deemed ineligible. Referred to in Jerry Garcia’s memoirs as “a vicious simpleton,” he nevertheless took up the guitar and began busking, with primitive yowlers like “Mr. Saigon” and “Hippy Dachau” anticipating punk rock by nearly a decade. Laramy’s music won him few admirers in the burgeoning counter-culture, but he was embraced by Hells Angels-affiliate Andre “Baby” Jane, who bought him studio time he used to record 1972’s Jungle Mower LP, a commercial failure. After an intense, inadvertent psychedelic experience at the Berdoo Angels’ clubbouse, Laramy’s music became more abstract, culminating in the geographically-confused psych-folk double A-side “Seoul Stealers” / “I Wished Upon a Machine Gun.” He disappeared in 1976. — J.M.F.

Key song: “I Wished Upon a Machine Gun”

Liesl Eddy

Alan Lomax called Liesl Eddy “the only woman prison singer who mattered.” Mississippi Fred McDowell called her “that miserable mute bitch.” Eddy was no one’s idea of a sweetheart, but even a cursory scan of her biography makes plain why she had to be tough. Raised Liesl Edzurbriggen by stern Swiss-German Calvinist tenant farmers in dustbowl-era Kansas, her parents forbade her from speaking in the belief that the family was being spied upon by papists. As she aged into young adulthood, Eddy’s muteness brought her into frequent, violent conflict with townsfolk in the nearby community of Arkansas, and she was eventually sentenced to eight years in prison after braining a local furrier with a cast-iron skillet.

Despite suffering from Marfan syndrome, Eddy was tremendously strong, and there was concern that she was too dangerous for women’s prison. Thus, in 1934 she became the only female inmate at Georgia’s notorious Lillyfold Penitentiary, where she worked breaking rocks on a chain gang. It was in prison however that Eddy’s unusual vocal talents were discovered. Despite her continued refusal to speak, she possessed a deep, southern-accented singing voice, and it was said that she alone could drown out a 20-man gang. Certainly it’s her lungs that stand out on the Lomax-recorded album of chain gang songs and spirituals Let Us Be Released (From Her) (1937), on which the tension between Eddy and her fellow prisoners is palpable.

Following a violent brawl that saw six men injured, Eddy was moved to solitary confinement, where Lomax was able to convince prison authorities to allow her use of a cigar box guitar. Eddy’s surprisingly vulgar, raunchy country blues tunes like “Hogmeat Driver Rag” and “No’ Mo’ Cone Pone” led the blushing musicologist to suppress her recordings for decades, though due to a clerical error “Liesl’s Idyll” was included on some early pressings of Lead Belly’s Negro Sinful Songs in 1939 before the mistake was noted. Eddy’s trail goes cold after her release in 1942, but following Lomax’s death her work was rediscovered. Her catalogue was issued for the first time in 2015 as Sugah On Mah Tongue: The Silenced Sessions on Lena Dunham’s Muff Trade Records. — J.M.F.

Key song: “Dog Done Had You Blues”

Cleodora Thanks

Raised by roving bead peddlers in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula, Cleodora Thanks relocated to Greenwich Village in the late 1950s and founded a rooming house where a number of the brightest names in folk music spent time, including Bob Dylan, Dave Van Ronk, and Horace Plenty. Although her cooking was so noxious Laura Nyro was reportedly briefly hospitalized by a casserole, Thanks was regarded as a mother figure by many of her tenants. Dylan made her the subject of his unreleased song “Big Momma I Don’t Know Blues,” while Joan Baez has claimed Thanks made uncredited contributions to a number of early Joni Mitchell songs. Thanks’ own culinary-obsessed music, which joins the earthy blues of a Bessie Smith with the subtlety of Bette Midler amid hints of gypsy jazz and klezmer, was largely unknown in her time, and she vanished in 1983 on her way to a state fair near Syracuse. New York-based archivist Karl Nard of Swede Nothing Records discovered a cache of unsold LPs in the basement of Thanks’ former rooming house after his uncle purchased the property. Thanks’ soon to be reissued work represents a crucial missing lunch in the story of mid-century American folk music. — J.M.F.

Key song: “Peanut Brittle Elegie”

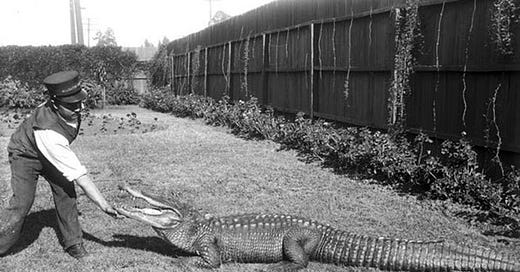

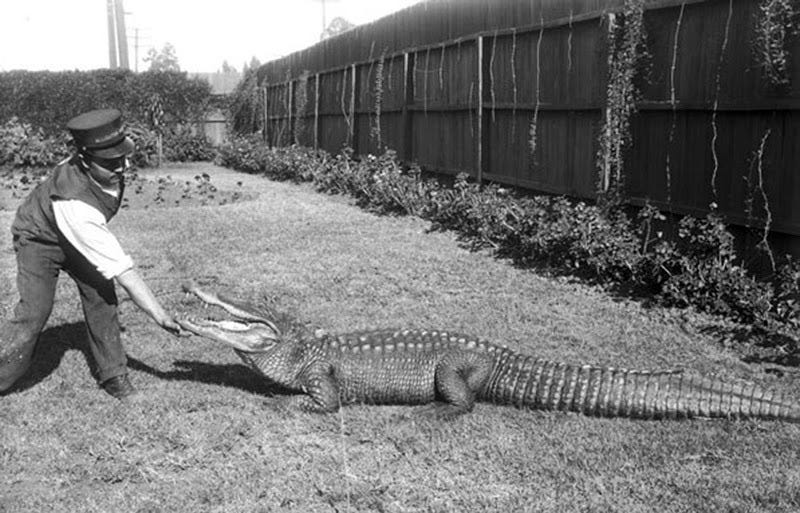

Jimmy Whaley the Folk-Song-Singing Crocodile

Jimmy Whaley was a crocodile that sang folk songs. Believed to be an urban legend for years until his existence was confirmed by Desmond Morris, the man who discovered an elephant who could paint and made a BBC documentary about how women don’t know what bicycles look like and want to have sex with horses. As Jimmy was only able to speak English while singing, most of what we know of his life is what has been parsed from those songs that have been tentatively identified as autobiographical. He was probably born in the Nile River, before stowing away in a cargo ship in the Suez Canal and making his way to Boston, and then the Appalachians, where he lived and sang for locals with a banjo he plucked with a back claw. His life was cut short when he was tragically shot after being speciesally profiled as an alligator by a poacher in East Texas. His remains are displayed at the Stephen Foster Folk Music Center in Chattanooga, Tennessee, in the form of a handbag. An anthology of Jimmy’s early work comprising several selections from the Great American Songbook, AmeriCroc, is forthcoming from Smithsonian Croakways Records. — D.J.C.

Key song: “America (My Country ‘Tis of Thee)”